© Vincent Debanne

Bâtiment d'Art Contemporain 28, rue des Bains 1205 Genève Suisse

The central exhibition in the 50JPG seeks to question the documentary character of photography. We all seem to share the assumption that anyone producing optical images is providing testimony on the tangible world. But this positivistic, pro-scientific nineteenth-century belief has been shaken by the ‘derealisation’ of our lives and the increasingly spectacle-oriented quality of news in contemporary capitalist society. Moreover, that process includes artists like Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman who reverse the usual codes in photography.

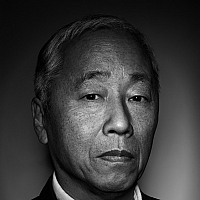

© Paul Graham

The exhibition fALSEfAKES seeks to probe the documentary value of photography. Whether we are producers or viewers of photos, we all seem to share the assumption that anyone recording images using an optical device is, in essence, providing testimony. That assumption is so deeply rooted that even today, photography is widely considered a prime vehicle for delivering irrefutable evidence. Emerging in the nineteenth century, photography quickly gained credence as a tool for furthering scientific endeavour, both in the social sciences – history, art history, anthropology, sociology – and the natural sciences. Moreover, this status was strengthened by the contemporaneous rise of positivism, a philosophy that viewed verified data received from the senses as the source of valid knowledge of the world.

© Jules Spinatsch

In present-day society, however, the ‘derealisation’ of human life has gone so far that it has become much harder to distinguish between real and fake, between documentary report and staged event. Unquestionably, still and moving images have a great deal to do with this blurring of distinctions, particularly because they are central to the spectacle-based perception that characterises today’s ultra-free market economy. A momentous shift occurred eleven years ago, when the United States went to war with another country on the basis of fabricated evidence, including photos. With such practices on the rise today, a vital question is who benefits from them. The answer is that by promoting the trend towards ‘spectacularisation’ of commodities, falsification serves the interests of the primary ideological prop for that trend – the bulk of the mass media – along with the interests of the military-industrial complex. But artists also resort to it. Ever since art as currently defined came into being during the Renaissance, they have continually used illusion and falsity to speak truth.

The problem in fact goes well beyond the ‘9/11 syndrome’ – an event often described as ‘larger than life’. Given that market society cannot realise its potential without reducing all aspects of life to spectacle, the false is a moment of the true. When commodities, or even false appearances, rule supreme – over everything from culture and love to health and the news, with ‘storytelling’ used to turn every event or experience into just another TV series – the terms ‘true’ and ‘false’ are voided of their original meaning and wind up with roughly the same standing.

© Stan Douglas