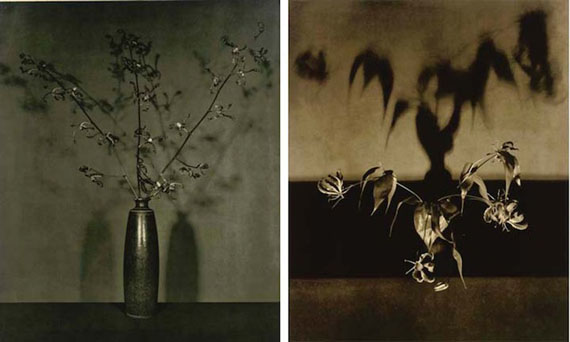

© Guido Mocafico

The term “still-life” originated in the 16th century in Netherlands and, by the 17th century, it had emerged as a distinct and specialised genre in Western painting. Many different types of still-life have developed since then, usually addressing the sensual perception of the viewer. Masters of still-life painting intended not only to create a hyper - realistic depiction of the world and to give a deceptively perfect illusion of reality, but to convey an often moral message through their use of certain symbols. For a vanitas theme, still-lifes often appear with aesthetically appealing luxury objects next to representations of mortality such as skulls, sand glasses, faded candles, withered flowers and broken glasses. Since the late 19th century still-life has gained great importance in artistic photography.

© Horst P.Horst

The title of the exhibition “The Art of Arrangement” highlights that, in photography, the creative process of the concept is just as important as the final photograph itself. The exhibition features timeless classics of still-life genre by photographers such as André Kertész, Aberlardo Morell and Horst P. Horst, as well as contemporary artists such as Veronica Bailey and Swiss artist Guido Mocafico.Guido Mocafico brings still-life arrangements of old masters to life in his studio. If one tries to understand the complexity of Mocafico’s still-life and landscape photographs, one soon finds out that the classical compositions of these contemporary pictures hold a very modern statement. On the surface, his work seems smooth and appealing, but profound themes about life, death and mortality become obvious upon closer inspection, just as they are in old master paintings. His works beguile the viewer, conveying both the illusion of being a painting while striving to depict the world as realistically as possible.

© Veronica Bailey

Many of Horst P. Horst’s works, including his still-life photography, reveal a masterful control of light and shadow as well as a striving sense for geometry, a rhythm of lines and contours. This is exemplified in the works “Classical Head with Flowers” and “Body Parts, Still Life”. In both depictions Horst arranges antique artefacts in dramatic light setting that stands out from the dark back ground evoking an atmosphere of timeless elegance and poise.

.jpg)

© André Kertész

Robert Mapplethorpe’s still-life photographs of surreal, amorphous objects are masterfully completed compositions filled with feverish, restless, overwrought tension, as is seen in “Flowers, 1984”. Mapplethorpe focuses on the play with sexual identity and roles. Just as in in his famous nude photography he uses symbolism to refer to topics such as gender, physicality and self-perception.Veronica Bailey’s Colourfields explores the theme of “renewal” by overlaying colour on to a still life landscape, complimented by references to the poem “The Autumn” by John Keats (1795 – 1821). Each of the sixteen artworks was titled with a line taken from the original prose. The images were created during the autumn of 2013 then reworked exactly six months later with Aniline dye inks. By transforming the original material, the works sought to be a metaphorical attempt to revive and regenerate the flora forgotten from a previous point in time. Yet the transformation process did not finish there; the pigment of these aniline dyes is temporary and its intensity decays rapidly. Therefore these reawakened, transient artworks were preserved in time though scanning and reproducing as lambda prints.

© Robert Mapplethorpe

Source : http://www.bernheimer.com