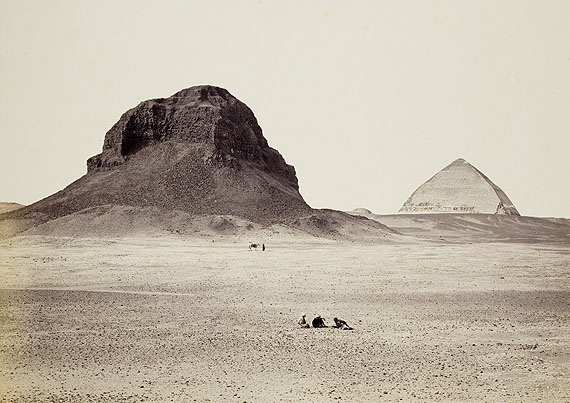

Fracis Frith: Dahshur, Pyramiden von Osten, um 1857 Museum Ludwig, Köln, Fotografische Sammlung (Sammlung Lebeck)

SK Stiftung Kultur Im Mediapark 7 50670 Köln Allemagne

The exhibition focuses on three classical travel destinations: Egypt, the Levant, i.e. Palestine and Lebanon, which were part of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, and the states of pre-unified Italy. The majority of exhibits show art monuments and landscapes, flanked by a number of photographs of daily life and portraits of individuals. The three regions are depicted in images that vividly portray their architectural subject or strikingly capture the atmosphere of the scene regardless of how well the site is known. During selection, special attention was paid to correlating the examples of architectural and landscape photography and making comparisons. Outstanding, compelling photographs have been obtained for the exhibition on loan from the rich collections of the Reiss-Engelhorn Museums(rem)/Forum Internationale Photographie(FIP), Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Fotografische Sammlung (Sammlung Lebeck/Sammlung Agfa) and the Historical Photo Archive of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum – Kulturen der Welt in Cologne, along with a small number of items from the Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur collection itself.

Travel photography played an important role as a genre even in the early days of the medium. Practitioners not only documented images of places, towns and rural landscapes but also architectural monuments and works of art as witnesses of cultural heritage. François Arago, presenting the daguerreotype at the French Academy of Sciences in 1839, specifically highlighted the process's major significance for academic disciplines such as archaeology. While early researchers had taken along artists and draftsmen to produce detailed images of the ancient sites and monuments, daguerrotypists and calotypists now travelled the Mediterranean to photograph historical buildings and art. Before long, the photographs ceased to be merely models or aides-memoire for painted or etched vedute; they assumed a commercial value of their own.

The Italian states held a magnetic attraction, just as they had for the painters and sculptors who had flocked there in the past. The large Italian vistas market was served not only by photographers based in Florence (such as Giacomo Brogi), Venedig (Giuseppe Cimetta) and Palermo (Eugenio Interguglielmi) but also by travelling photographers from Central and Northern Europe. Some, like James Anderson or Giorgio Sommer, transferred to Rome or Naples altogether.

At the same time, a number of photographers travelled to North Africa, Syria and Palestine or even further afield. Many of the earliest travel photographers were very well-off individuals or were sponsored on their trips. Mostly from England (like Francis Frith), Germany (Jakob August Lorent) or France (Maxime Du Camp and John B. Greene), they travelled through Egypt and the Middle East, either on a mission for the government back home or driven by their own enthusiasm. En route, they found pyramids, ancient temples and other witnesses of thousands of years of civilization, discovered the Orient as the quintessence of exotic flair and fascination or visited the sites they knew from the Bible. They brought their photographs back to Europe and published them in elaborate and exclusive portfolios or albums.

Around the middle of the 19th century, travel photographs were produced by only a few pioneers – often under extremely tough conditions. It was not until the second half of the century that professional studios were established offering photographs as souvenirs for the privileged minority in a position to travel to distant lands.

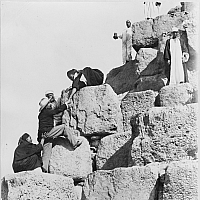

Taking photographs was difficult in those days, especially in a hot desert climate, and few of the photographers had the benefit of any technical training. All the more reason to admire the results they achieved – showing monuments that are now a great deal more weathered or have disappeared altogether. A travelling photographer around the middle of the 19th century toted a great deal of baggage. Because enlargements were hardly possible, the negative had to be the same size as the final print, so several cameras were often needed. He also carried a full set of laboratory equipment and a dark room. Only with the advent of ready-to-use dry plates and ultimately the silver gelatine negative could processing be postponed and performed when conditions were more favourable, which made life a great deal easier for the photographers of the second half of the century.

The travel photographer's subjects included all sites of historical or cultural significance as well as picturesque places that tourists wished to see and remember. Local people often appeared in the photographs, enlivening the scene and at the same time enabling not just the shapes but also the scale of gigantic columns and sculptures to be appreciated. Because of the low sensitivity of the photographic materials, exposures were still relatively long, despite intense sunlight, and scenes in early photographs seemed static and contrived. Portraits of individuals or small groups of religious leaders, noble chieftains, merchants and craftsmen or women in veils with their children were arranged in the studio. Some particularly fine examples of this portraiture came from the studio of Pascal Sébah.

Focusing on three regions and the work of selected photographers, the Historical Travel Photography 1850-1890 exhibition attempts to highlight the diversity of travel photography in terms of its imagery, formats, techniques and forms of presentation. Against the backdrop of the two concurrent exhibitions, the photographs from Italy over the last century permit a direct comparison with those of August Sander and Ruth Hallensleben, e.g. in Pisa, Amalfi and Venice.