Paris-Beijing Photo Gallery The Old Factory 798 Art District, Dashanzi, Jiu Xian Qiao Lu n°4, 100015 Beijing Chine

Essay by Romain Degoul, Beijing, January 10th 2009

Paris-Beijing Photo Gallery is proud to present the works of Hei Yue, Li Wei and Liu Bolin in the group show « Incarnations ».

Incarnation as a person is the manifestation of an abstract notion through human characteristics; here, it is evidently the social and political scopes that are personified through the artists’ bodies.

Following the legendary first generation performance artists from the Yuanmingyuan artist village such as Zhang Huan, Zhu Ming and Ma Liuming, the celebrated artists Hei Yue, Li Wei and Liu Bolin are the present force pushing the boundaries of Chinese contemporary photographic performance. Unrestrained by their given titles as photographers and performers, all three artists are also established sculptors. The correlation between them is not only that of friendship, but they share the same aspiration to create art using their own bodies. Filled with symbolism, the artworks reveal a fierce criticism of politics, power and propaganda as well as the determination to denounce social issues that are tearing their country apart and could jeopardize the future, its future, our future…

By using the universal body language, the tactful, subtle, and sometimes even naïve symbols clearly convey their messages and allow audience from any where in the world to decode them.

In Li Wei’s “Falls,” one of his most representative series, the artist falls from the sky in random places with his head hidden, stuck in the ground. China’s rapid changes have led to major conflicts and problems that are too intense to experience, better to hide from the difficulties and avert the conflict like an ostrich. Hiding is a typical behavior in China where nothing is expressed directly; any sort of disagreement will be oblique, alluded and never explicit, and nobody wants to break the social rules.

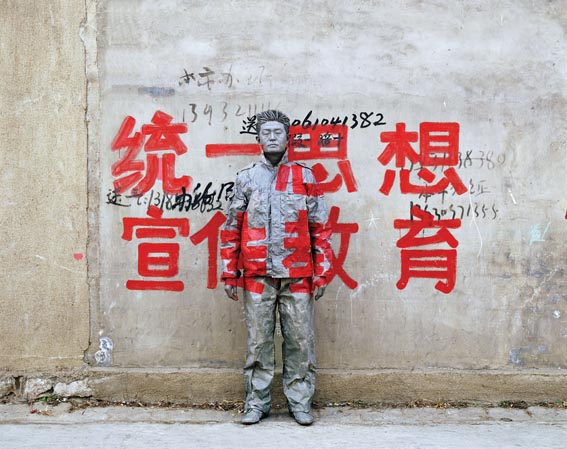

Hiding is also a recurring theme in Liu Bolin’s works, both in his sculptures and in his acclaimed series “Hiding in the city.” The artist paints his own body in order to dissolve into different backgrounds and cityscapes. He places himself as a disappearing human being in an actual landscape as if he was dominated and finally devoured by his environment.

Liu Bolin’s vanishing act generates a powerful and tragic relationship between the subject and his surroundings: damages had been done on both of them. Whether it is when he stands in front of the famous propaganda slogans painted on public walls throughout China or the story behind “The Suojia Village” picture, which was taken while the place was being destroyed, and from where he has been obliged to move a few weeks later with friends and neighbors.

The contradiction that human development could be the origin of human ruin is strongly expressed: do we exert the domination or are we the ones that are being dominated?

This questioning about domination and authority is also a pillar of Hei Yue’s reflection. In his body of works “…123…”, Hei Yue often positions himself in front of figures of authority showing the audience only the view of his back with naked buttocks and spanking himself 123 times while the photograph is being taken. It again questions the symbols of authority and tradition, confronting the conservatism to the modernity in this complex society where social interaction becomes the instruments of manipulation.

Hei Yue is deliberately not showing his face in a society obsessed by the face and where all is about not losing it. One must keep an air of composure, like a mask in order to deceive his interlocutors about his true feelings.

Another way to hide…

In front of this oppression, Hei Yue chooses naivety and humor. Wearing the traditional split pants that all Chinese children wear, and in the presence of an authority, he decides to spank himself for his insolence and refusal to adhere to the rules and doing by so, seems to raise the question “who has the right to discipline and punish?”

Throughout the times, dogmatic discipline and authority have always been difficult for artists to endure. In a country like China, one can understand easily the underlying depths of meaning in this statement. Without any purpose of criticism, “Incarnations” embodies the concerns and response of the three exceptional, over-creative, socially and politically engaged artists to the disruption of their culture, their society and their country.