© Hugh Owen

Of all the people critical to the story of the introduction of photography, the one with perhaps the most humble beginnings is Nicolaas Henneman, who was born in the Netherlands in 1813 and was a valet to William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877). It would have been natural for the founder of photography to call on his valet to fetch chemicals and to set up cameras, but Henneman rapidly emerged as a working partner, making prints and even making his own negatives.

In 1841 or 1842, when Talbot and Henneman were working together to master the new calotype negative process, Henneman was a convenient volunteer for a photographic portrait. The resulting picture, a calotype negative, shows Henneman’s strong and determined demeanor and is a fitting tribute to Talbot’s most trusted assistant and supportive friend and colleague.

© William Henry Fox Talbot

In addition to Henneman’s portrait, Talbot’s work at Hans P. Kraus Jr. Fine Photographs includes a salt print of Lace. The negative for the print was made without a camera by placing a piece of lace on a sheet of photographically sensitized paper, casting its shadow and producing the boldly graphic image. When Talbot first held it in front of a group of people, they thought it was an actual piece of lace and were stunned to learn that instead it was a photographic representation. These photographs could record a level of detail comparable to that seen in still-lives rendered by the most accomplished Dutch painters.

Another photographic image made without a camera, is a poetic photogenic drawing of Leaves of Grass by Henneman from March 1839, within two months of when Talbot announced his invention to the world.

In late 1843, Henneman began a bold venture, the world’s first photographic printing firm in the town of Reading. Talbot supported this new venture by commissioning prints for his pioneering publication The Pencil of Nature (1844-1846), the first commercially published book illustrated with photography and the first mass production of photographs. A salt print of Westminster Abbey, prior to May 1844, is the only known image contributed by Henneman to The Pencil of Nature.

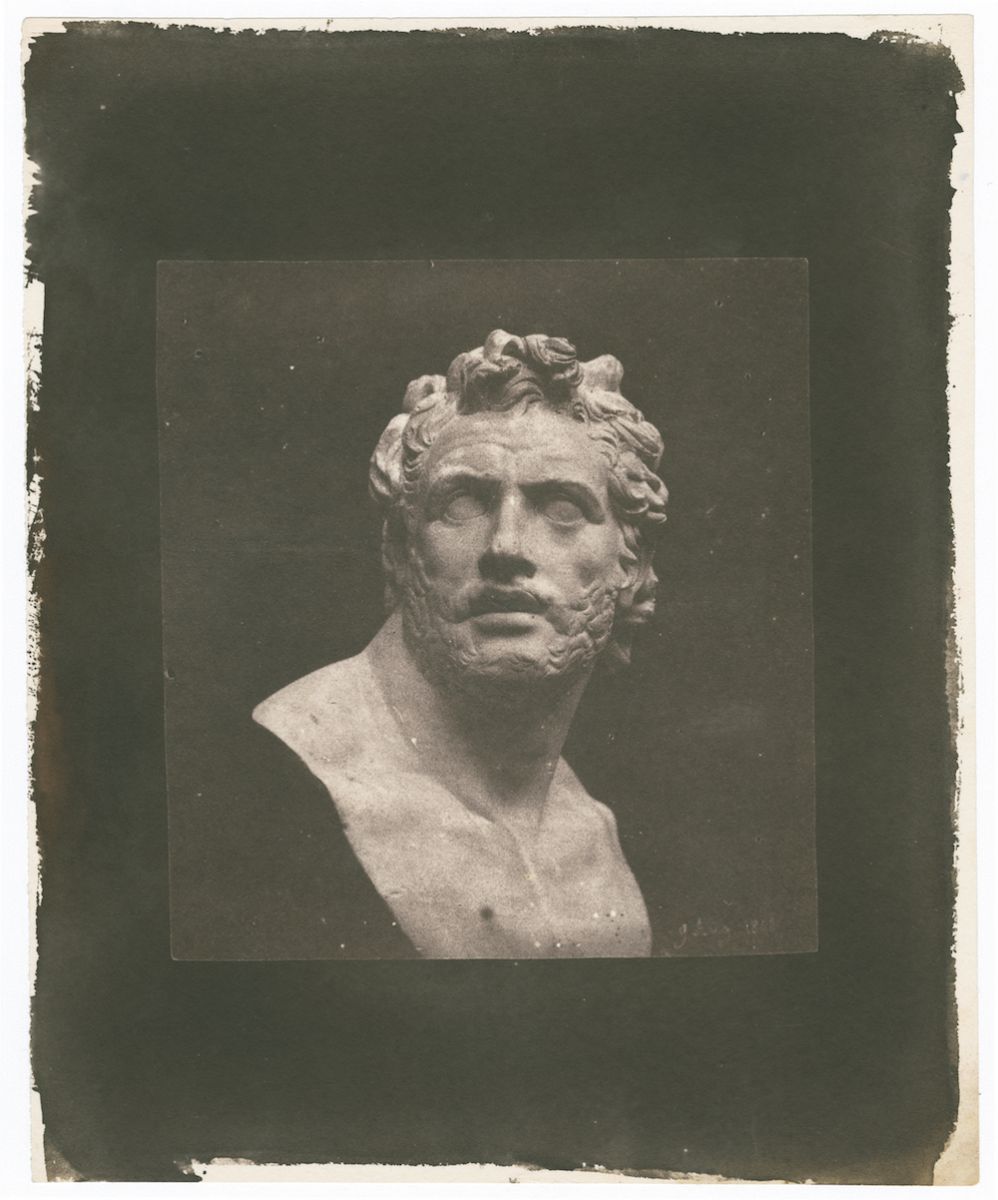

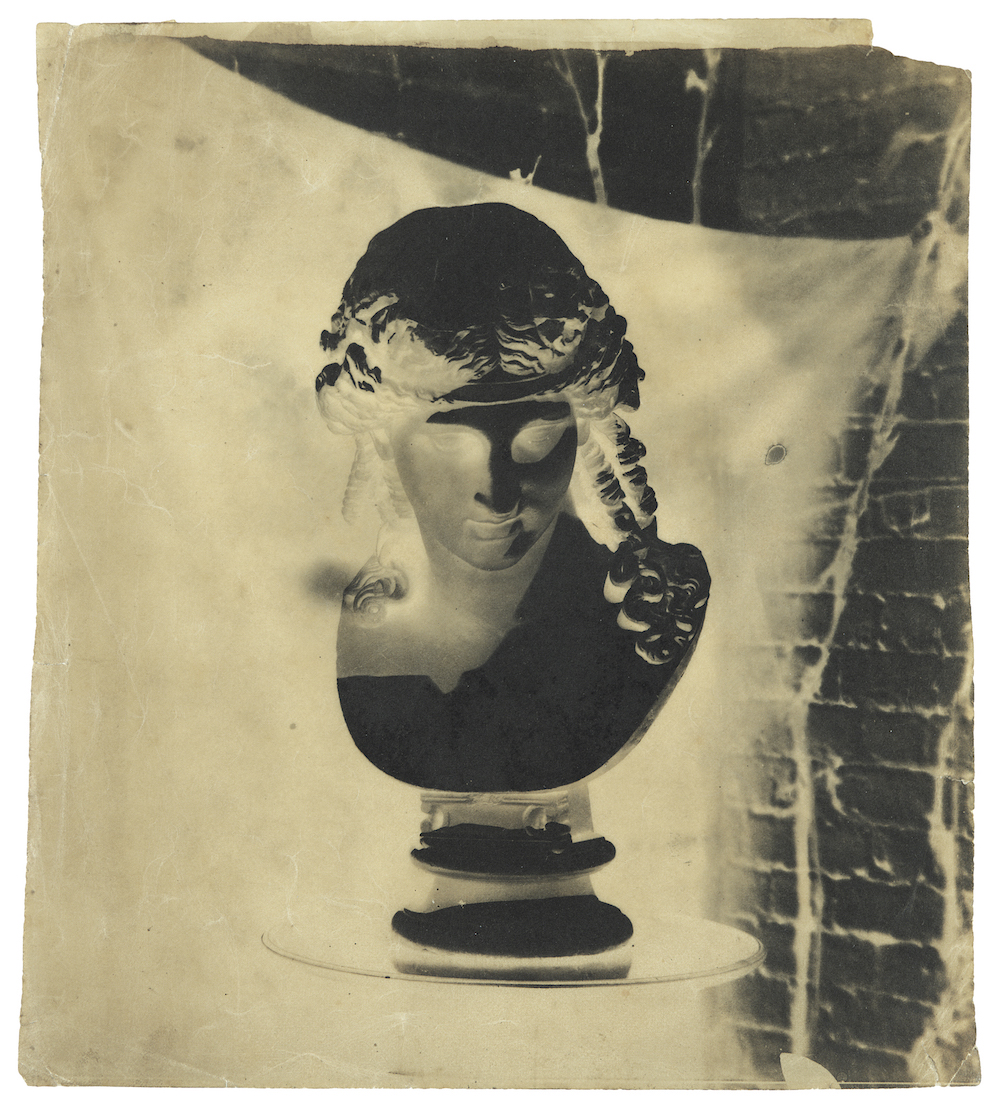

Two sculptural heads come to life in the hands of Talbot and another early British master, Benjamin Brecknell Turner (1815-1894). Talbot’s Bust of Patroclus, a salt print from 1842, showing his plaster cast of the ancient marble sculpture in the British Museum, is included in The Pencil of Nature. Turner’s calotype negative of the Bust of Dionysus, from the early 1850s, is of a plaster cast modeled on the sculpture of the Greek God of wine (and the patron of the theater) from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

© Benjamin Brecknell Turner

Known for finely composed and exquisitely rendered photographs, Hugh Owen (1808-1879) was a master of the paper negative, having learned directly from Talbot. Owen’s day job, a cashier for the Great Western Railway in Bristol, stood in stark contrast to his photographic accomplishments, which brought him acclaim in the 1840s and 1850s. Harvest scene with stooks and trees, an albumen print from the 1860-1870s, evokes atmospheric harvest scenes by Constable or the Barbizon School painters. Owen’s work was recently on view at Hans P. Kraus Jr. Fine Photographs in New York and marked the first exhibition of photographs by Hugh Owen since the 19th century.

In 1858, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Cherbourg to attend the grand opening of the newly engineered naval port designed to accommodate France’s modern fleet of battleships. A seascape by Gustave le Gray (1820-1884) recorded the official royal event that day, with French ships in formation greeting the royal couple, seen reviewing the fleet from the safety of their steam-powered yacht.