© Jackie Dewe Mathews

Trafficantes: Foreign Women imprisoned in Brazil for drug trafficking.

By Jackie Dewe Mathews

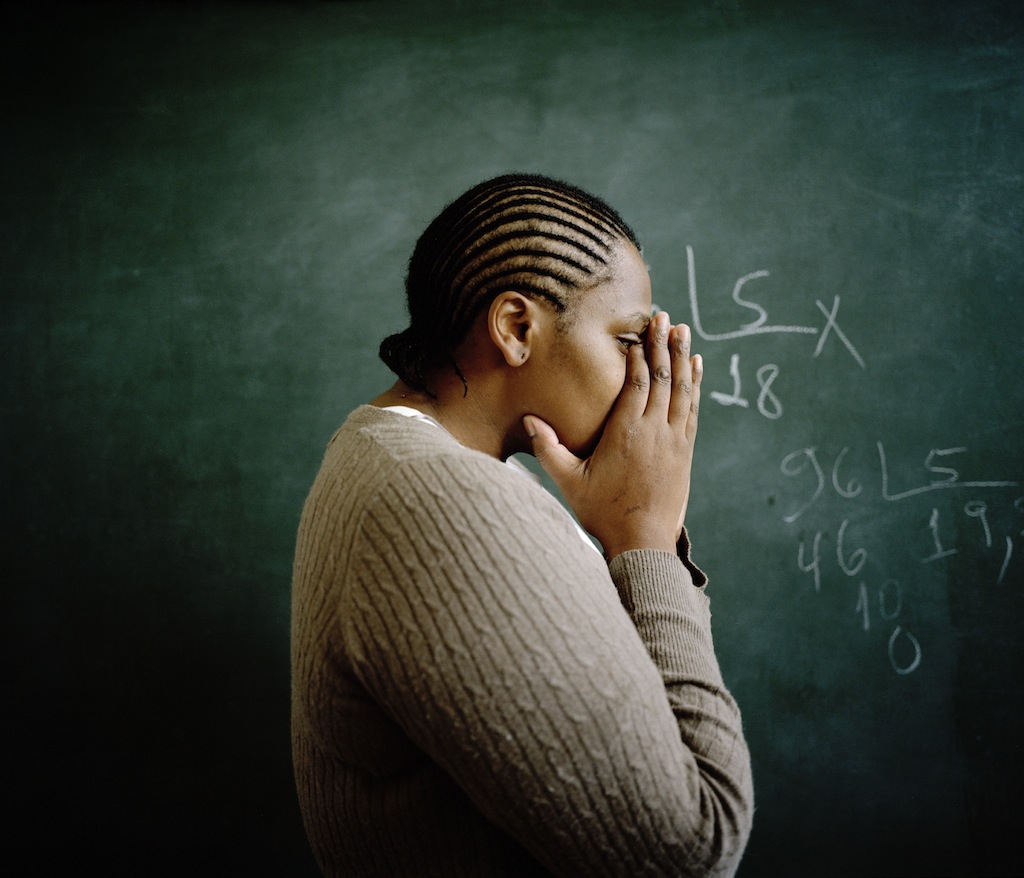

“You cannot say any woman who does this is a greedy woman or a cheap woman. If you look at the women here and you listen to their stories, you will see these are mothers, sisters and wives. People that had decent lives but circumstances drove them to do this.” South African prisoner at Sao Paulo Capital Penitentiary for Women.

Sao Paulo Guarulhos International airport is the main exit point for drug mules carrying cocaine from South America to the rest of the world. With flight connections to 53 other countries, it is well positioned to supply the increasing global demand for cocaine. On average, five people a day are arrested there for international drug trafficking.

Less than 10 years ago there were only 40 foreign women imprisoned in the state of Sao Paulo. In response to the swelling numbers of recent years, all foreign women have been moved to the Capital Penitentiary for Women, where currently, at more than 400, they account for over half the prison population. The largest numbers come from South Africa where a widespread drug problem, together with a large gulf between rich and poor, has created an environment where women are prepared to take a huge risk in order to earn quick money. Yet these women see very little of the real profits of international drug trafficking and, if caught, face long sentences of 3 to 15 years in a foreign jail, far away from their home and children and with the right to just two phone calls a year.

The penal system in Brazil, a legacy from the Portuguese, is slow and cumbersome. After arrest, these women can wait between two and six months for their court hearing and up to a year to receive their sentence.

The law against drug trafficking is so vague and open to interpretation that sentencing is often influenced by the mood of the judge in court that day, which can mean the difference of several years.

After completing two thirds of their sentence, prisoners have the right to conditional freedom or parole. They are free to leave the prison but must finish their sentence in Brazil. However, as a foreigner, without family, a place to stay or the correct papers to work, outside can be a dangerous place. In 2006, a shelter was set up by Catholic nuns in response to what they saw as a lack of support from the state or foreign consulates, for their nationals once outside prison. The biggest problem they found was the issue of affording a flight home for prisoners who have completed their sentences. Some women were even committing the same crime as the only means to finance their return journey.

In contrast to the perceived profile of the repeat offender who is fully aware of their actions and seduced by material wealth, many of the women in prison for drug trafficking, have never committed a crime before. A series of misfortunes resulting in extreme poverty mostly provided the motive. Often being a single parent responsible for several children and sometimes even the sole provider for three generations of family can have become a financial burden too much for them. They took up an offer that came at exactly the time when they needed it most and that was presented to them in a way that was risk free. Traffickers, skilled in identifying desperate and vulnerable women, promised them that they had good relationships with police and airport officials and that nothing could go wrong. But many of these women were never meant to succeed. Before they even reached the airport, an anonymous phone call, supplying their name and description, was placed to the police – often by the very same people who had employed them to carry the drugs – (for the most part, Nigerian men, who are in control of the business in Brazil) as a ploy to detract from a more lucrative load.

Unfortunately, the money on offer (between £500 and £6,000, for anything between half a kilo and 12 kilos, depending on the countries travelled) can change the life of a person with nothing. So the women keep on coming.

Because for every one that is caught there will be others who get through and so there will always be new girls to replace the ones who are imprisoned and they will continue to be treated as expendable by the men who send them.

© Jackie Dewe Mathews

All photographs were taken in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 2010.

Captions:

From Portugal, awaiting sentence, has served 10 months.

Blackboard in English classroom.

Prison uniforms.

Inmates work for $150 a month, not enough to save for a ticket home.

This South African spoke to her children only 7 months after arriving in prison.

From Russia, sentence: 5 years and 8 months, served 1 year and 7 months.

From Philippines, sentence: 5 years and 3 months, served: 1 year and 3 months.

"You only have God in a place like this, nothing else.”

From South Africa. Died in prison 12/11 while serving a 4 year sentence.

From Peru, sentence: 8 years, served: 1 year and 3 months.

Jackie Dewe Mathews was born in London in 1978. Following a degree in philosophy she worked in the film industry as a freelance camera assistant on feature films and commercials.

Her continued interest in cinematography has informed her photography practise which she was able to develop during an MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at the London College of Communication in 2007. Since graduating with a distinction, she has had work published in the Saturday Telegraph, the Sunday Times, The Guardian, The Financial Times, Stern and The Fader Magazine. In 2008 she was awarded the Joan Wakelin bursary for a social documentary project from the Guardian newspaper and the Royal Photographic Society. In 2009 she was selected by the Magenta Foundation for emerging photographers and received a honourable mention at the New York Photo Festival and the International Picture Awards. In 2010 and 2011 she was a runner up in the Ojodepez human values award.

Photo et vignette © Jackie Dewe Mathews