MKgalerie Berlin Rotterdam Rudi-Dutschke Strasse 26 10969 Berlin Allemagne

The exhibition FAIL AGAIN FAIL BETTER#2 brings together the work of several diverse artists. What they have in common however, is a more than usual interest in the condition of the human being; his shortcomings and, at the same time, his relentless determination to keep on trying. Just as in the well known texts of Samuel Beckett, the master of absurdist theater, the situations are sometimes tragic, sometimes comic and preferably, they are both at the same time. FAIL AGAIN FAIL BETTER#2 is not only about failure, but it is also about the human compulsion to strive for improvement despite the knowledge that perfection is unattainable. The exhibition does not desire to illustrate a theoretically founded concept but aims to bring together an associative, loosely defined collection of noteworthy works from recent and less recent times.

FAIL AGAIN FAIL BETTER #2 was curated by Martijn Verhoeven. Verhoeven is an art historian and freelance curator, based in Rotterdam. He teaches art history and theory of photography at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, the Netherlands.

The work of Bas Jan Ader can be construed as the starting point of the exhibition. Ader (1942-1975) counts as one of the most captivating Dutch artists of the second half of the twentieth century. In his small, but to this day intriguing body of work, falling plays an important role. This orchestrated falling (and they are orchestrated as he consciously endangered himself with each fall) remind some of the early slapstick films of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin who, along with others, continuously sought out the tension between the comic incident and the tragic outcome, the absurdist creativity of everyday fortune. But Ader avoids the outspoken comic effect in his work. His movement and facial expression, other than the grotesque acrobatics of slapstick, are grave and isolate the comic tendency of misfortune. Piece for piece the films of Ader are a witness to the existential earnestness that emphasize human mortality. The 16mm film shown during this exhibition, Broken Fall (organic) Amsterdamse Bos-Holland (1971), might be the simplest and yet strongest metaphor for failure. We see Ader hanging from a tree branch above a canal until his strength leaves him and he splashes into the water below. Repetition of this short film is essential: each time he lets go and falls into the water. As if he has borrowed the words of Beckett in Worstword Ho: “No matter, try again, fail again, fail better.”

Zaida Oenema (1980) - who happens to be an admirer of Ader - shows moments from her ordinary every day life (actions, objects, thoughts) which she modifies just enough for them to lose their logic and normality. Her photo and video work is characterized by a dry sense of humor in which we see how individuals function within contemporary society full of unwritten and written rules, conventions, expectations and assumptions. She holds a mirror up in front of the viewer and asks the question: do you develop an obsessional neurosis to keep a grip on your life or do you become paralysed by your self awareness? Wonderment coupled with irritation for today’s western society - where individualism and consumerism are the norm and deviation from that norm are quickly viewed with incredulity - are important motivations for her work.

In the often spectacular video installations of Matthijs Rensman and Alexandra Werlich (both 1981) improvisation plays a central role. Rensman and Werlich work with amateur actors (often friends and family) and without a set script. Their choice of this method results in the accidental uncovering of implicit, subconscious role patterns: mistakes made by the characters when they fall out of their roles give an insight into the intersubjective structures which play an important role in our society. Front and backstage become temporarily and simultaneously visibleto the viewer. Almost all of their work displays an open and at times outspoken comical quality but, on closer inspection harbors a darker undercurrent.

In her drawings, Nare Eloyan (1988), who graduated this year from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in the Hague, uses the attractive language of comics and cartoons, an international language which is easy to read and suggests childlike innocence. She ensures the viewer is drawn to the work but once the viewer is engaged she shows her work’s content is all but childlike and innocent. Not the super heroes - the individuals who havemade it and are successful - occupy the landscapes of Eloyan. Instead she often portrays the failures and pathetic characters who haven’t made it and struggle on their way along the road to their next failure. In the words of Eloyan herself, “the artwork could be the masochist and the viewer the sadist.”

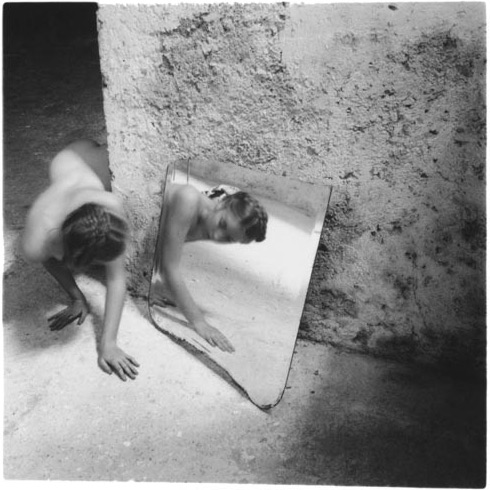

From an artist who died well before her time - Francesca Woodman (1958-1981) - the exhibition displays several photographs. Woodman invariably shows the near intimate relationship between her (often naked) body and the indeterminate domestic spaces which appear to give life to her photographs: the wallpaper slowly loosens from the wall; the frame of the fireplace appears to move between her legs; or a hand protrudes through the wall. She plays these complicated games with the space in order to compare the fragility of her own body with the quality of the powerful objects around her. And sometimes Woodman actually becomes part of the wall under the wallpaper or a piece of the floor. Moreover, we should not forget that Woodman was both photographer and model. In this she orchestrated that which happened in front of the camera as opposed to documenting what happens to occur as many other photographers do. A method she has in common with Bas Jan Ader.

Finally, Ene-Liis Semper (1969) also uses herself as a point of departure in her work. With a sharp eye for the mental and physical experience, she aims the camera on intimate aspects of her personal life. The resulting images have little in common with the typical documentary-like images which have been popular in the arts in recent years. On the contrary, Semper captures subtle moments in a private setting to subsequently isolate them explicitly bringing them somewhere outside of the every day experience. This is the reason Semper’s videos are always more than mere registrations of a performance. By playing with the images, rewinding them or playing them in slow motion, she is able to achieve a thorough analysis of the comparatively tragic aspects of her (and the viewer’s) life.