Haus der Kunst Prinzregentenstrasse 1 80538 Munich Allemagne

"Best museum exhibition"

(Kenneth Baker's top 5 art picks for 2008, in: San Francisco Chronicle, January 2009)

William Eggleston's early photographs were black and white. In the 1960s he began to photograph in colour and - almost single-handedly - heralded in the era of fine art colour photography. A solo show at the MoMA in 1976 made him famous. Eggleston's snapshot aesthetic and his psychologising use of colour was still unusual at the time; in an annual review, the MoMA show was even called, "The most hated show of the year." Today Eggleston enjoys a cult status among younger generations of photographers and film directors.

The exhibition traces Eggleston's artistic production from his early black and white photographs and his pioneering shift to colour photography to the present. Included among the 160 exhibition pieces are rarely published and exhibited works, as well as some that have never been on view:

- early black and white photographs from 1961-68

- 25 original dye transfer prints from "William Eggleston's Guide" from 1969-72

- the video diary "Stranded in Canton" (1973-74, video, b/w, sound, 77 min) about Eggleston's legendary nocturnal excursions

- 15 exhibition prints from "The Democratic Forest" created in the 1990s

- 12 digital prints from 1999-2001 (premiere)

- 20 exhibition prints from "Election Eve" from 1976 (premiere)

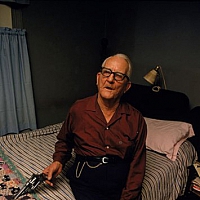

William Eggleston still lives in Memphis, where he was born in 1939. He spent his childhood in Sumner in Mississippi. His family was well off thanks to the cotton plantations they owned. William Eggleston never had to earn his own living and was thus able to devote his time to his own interests: music and photography, film and sound technology. He did not conform to social norms, and, although fashion in his day was becoming more and more informal, he usually wore a suit. His serious appearance, however, contradicted his unconventional behaviour. His work clearly reflects the fact that he was a free thinker who acted independently - "a rebel who looked like a silent film actor, who was partial to alcohol, drugs and beautiful women" (Thomas Weski).

Eggleston's earliest images are raw, sketch-like black and white photographs of scenes in Sumner, Mississippi. They give the viewer the feeling that Eggleston simply casually selected the scene and accepted everything that took place in the defined framework. The result is photographs that integrate the incalculable in their composition, thus accepting coincidence. The belief that the uncontrollable quality of the moment enriches the fixed image was one that Eggleston shared with Henri Cartier-Bresson. In 1959 Eggleston discovered the Cartier-Bresson's monograph "The Decisive Moment", published in 1952; the book became Eggleston's photographic point of reference in the years that followed.

Eggleston's central theme is found in the everyday life that surrounds him: supermarkets, which were built in urban outskirts; sidewalks, driveways, terraces, polished automobiles, set dinner tables, gas stations; middleclass homes and southern interiors; bars and their regulars. Everything that takes place in front of the camera is essentially worthy of being photographed, regardless of how irrelevant or trite it may seem. A stuffed freezer or shoes underneath a bed - Eggleston directs his 'democratic' gaze towards everything and treats it all with the same attention. His focus is on places in his hometown, in Memphis, New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta; he also, however, travels around the globe for commissioned works.

With his focus on everyday life, Eggleston set himself clearly apart from the elevated motifs of the master photographers of the time who had to work very slowly and carefully because their plate cameras could only be used with a tripod. The works of the leading photographers of the period, such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, were characterized by severe composition, brilliant handling of photographic techniques and the treatment of classical subject matter - majestic landscapes, idealized portraits and nudes. William Eggleston, by contrast, used various types of cameras, from small and mid-sized formats to large ones. Following his shift to colour photography, he also experimented with different methods of production, from drugstore and C-prints to dye transfer printing.

His discovery of dye transfer printing became decisive for his artistic course. This was a technique developed by Kodak in the 1940s in which the motif was transferred onto a paper surface from three successive negatives. The result was a relatively permanent colour print in which the individual colours could be altered or intensified without influencing the complimentary colours. Eggleston was thus able to orchestrate the individual elements of the colour scheme; above all, he could also influence the emotional content and the psychological effect of his images. In this way, the warm afternoon light lent the portrait of a supermarket employee a conciliatory touch while it simultaneously cast a sobering glance on the American dream.

The photographs are often taken from unusual perspectives. Lying on the ground, Eggleston photographed a tricycle, thereby citing a child's still unrestrained, free gaze on an object that can develop several different meanings through play. The image conveys this openness with regard to interpretation and takes the viewer back to his own childhood. The monochrome shot of a red ceiling became an icon: a blood-red sky, photographed from a housefly's perspective. Many of the artist's most powerful images display a similar suggestive effect. With alarming strength, they surpass themselves and can invade the subconscious to such an extent, that the actual object is only perceived as a motif defined by the artist.

As familiar as the motifs are to the viewer, Eggleston's series of everyday scenes resist a quick and clear interpretation. With their unconventional perspectives, the selected scenes and the subjective use of colour, the images free the way for additional associations and meanings. Through the abundance, or over-abundance, of the range of items for sale spread out before customers and consumers, atmospheric images are created that certainly make a point about the symptoms of a mass society and the state of mind of the individuals in it. Loss, estrangement, loneliness and desire are exposed as contemporary phenomena in many of his photographs.

Stranded in Canton

"Stranded in Canton" is a portrait of a dazed subculture in which Eggleston was both a participant and observer. Eggleston made films with infrared material - usually at night and using only the existing lighting - on streets, in bars and apartments and at concerts. Without editing, he filmed monologues of friends and strange actions. He exposed the entire length of the video tape when doing this. Many of the protagonists - musicians, male chauvinists, a transvestite - were drunk or on drugs. The photographer also filmed his own children early in the morning when they were in that spaced out condition between sleep and waking. The camera work was both confrontational and evasive: it literally scanned its objects only to then retreat and to grasp and circle them in endlessly long shots. The black and white video material was created in 1973-74 in Memphis, New Orleans and other areas in the South. It was recently rediscovered and compiled into a narrative format by Robert Gordon. Until then the films had remained fragments that had only been shown a few times at festivals.

The retrospective is developed in close cooperation with the artist and is a coproduction with the Whitney Museum of Art, where it opened on November 7, 2008; the show is curated by Elisabeth Sussman of the Whitney Museum and Thomas Weski of the Haus der Kunst. The presentation in the Haus der Kunst is the show's only European station. It will then return to the United States and be on view at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

"William Eggleston. Democratic Camera. Photographs and Video, 1961-2008"; with contributions by Thomas Weski, Elisabeth Sussman, Donna De Salvo, Tina Kukielski, Stanley Booth and Adam Welch; 304 pages, ISBN 978-0-300-12621-1, Yale University Press, € 49,80