HackelBury Fine Art Ltd. 4 Launceston Place W85RL London Royaume-Uni

Now 98, Willy Ronis is a key figure in humanistic photography. Since the late thirties, his poetic images have immortalised many magical moments of everyday life, and are recognised worldwide. Last year more than 500, 000 people visited a major retrospective exhibition of his work in the Hotel de Ville, Paris.

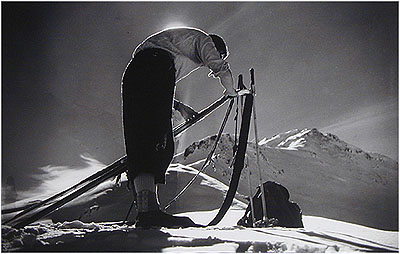

We are delighted to introduce here previously unseen works, and present the secret lifelong passion of Willy Ronis: the mountains. His love of nature and the great outdoors are revealed, demonstrating what he describes as a love affair with this majestic landscape. Far from the cities and factories that he glorified throughout his career, he found a completely different perspective: no less powerful, and perhaps more intimate.

Willy Ronis was born in Paris in 1910 to Russian parents. His father was an able photographer and skilled retoucher, and his mother a pianist, who encouraged Ronis to play the piano and violin from an early age. Pupils at the lycée he attended close to his home in Montmartre, were given weekly days off for religious instruction. As neither of Ronis’ parents were particularly religious, Willy was able to spend his free time visiting the Louvre where he was fascinated by paintings of the Dutch and Flemish schools of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries which would later emerge as influences in his photography of the nude and in his handling of crowd scenes and landscapes.

His father ran a modest photography studio, catering to the portrait requirements of the French Bureaucracy and from 1924 onwards, Ronis helped in the studio darkroom until his father was forced to stop work due to ill health and Willy had to run the studio single-handed. With the death of his father in 1936, Willy was forced to sell the studio, which was to prove a major turning point in the life of the young photographer. He had been able to salvage some photographic equipment from the sale of the family business and a small amount of industrial & commercial work came his way. He also started to make photographs of his interests, such as skiing and climbing, which he began to sell to the small but growing market based on winter sports.

Willy also began to take on a small amount of freelance reportage work. He recalls that he was not interested in Hard News as such, but it did enable him to obtain a press pass, which allowed him access to more interesting and challenging situations.

After the war, Ronis dedicated himself to documenting the everyday life and hardships of the French people. Whilst Henri Cartier-Bresson, with the Magnum Agency, was travelling across the world working on an international scale, Ronis and his great friend Robert Doisneau, who both worked for the Rapho agency, concentrated their energies on recording the psychological and physical reconstruction of France and continued a systematic documentation of different working districts in Paris. In 1947, Ronis was awarded the Prix Kodak and when the Museum of Modern Art planned a major exhibition in 1951, curated by Steichen and titled Five French Photographers, Willy, along with Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau and Izis was invited to send 30 prints of his own choice to New York for inclusion in the show.

Ronis frequently worked for the left-wing press covering strikes, human-interest stories and disasters. However, in 1955 he left the Rapho agency because his photographs of an industrial dispute were used in a travesty of his own views and intentions. As a result of his refusal to compromise, commissions became very scarce and he was forced to move south with his wife, Marie-Anne, where he supported himself and his family through teaching.

In 1970, Ronis rejoined Rapho and from the middle of that decade a new generation began to recognise the importance, both historically and actually, of Ronis’s work and his place within the development of photography was assured. The quality of Ronis’s work had also been recognised at a more official level and in 1980 he was asked to make a donation of his negatives to the French State, which has a scheme under which important artistic collections are safeguarded for posterity.

Willy Ronis has received the fruits of his work quite late in life, in part because of the great wave of nostalgia for the black and white images of the seemingly golden age of urban community of the 1940’s and 1950’s. Ronis’s talent is the ability to convey in a few images the essence of a whole way of life and to conjure pictures from a simple subject matter, which are layered with an almost infinite depth of meaning. The photographs communicate a warmth and sympathy for his subjects, despite the apparent ease with which we can read their meaning. They are never banal or sentimental and fully deserve to be ranked amongst the best work of twentieth century humanist photography.