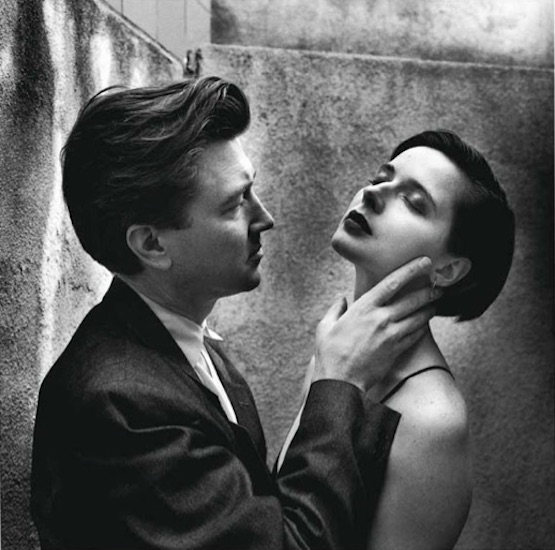

©Helmut Newton David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini, Los Angeles, 1983 (detail)

Expositions du 2/12/2014 au 17/5/2015 Terminé

Helmut Newton Foundation Jebensstr. 2 D-10623 Berlin Allemagne

When Helmut Newton launched his foundation in Berlin in the fall of 2003, he donated several hundred original photographs, which have since been kept on permanent loan by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Now for the first time, on the occasion of its tenth anniversary, the Helmut Newton Foundation is presenting over 200 photographs from this collection, under the title “Permanent Loan Selection”. The three main genres – portrait, nudes and fashion – will be presented in separate rooms, along with numerous photographs in various formats that have not yet been shown in Berlin. These include a number of "vintage” or “late prints" – original prints authenticated by Newton himself.Helmut Newton Foundation Jebensstr. 2 D-10623 Berlin Allemagne

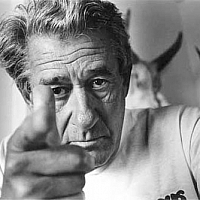

Helmut Newton has a rare and distinctive sense for situations and moods. He famously avoided working in the studio, choosing instead to shoot on location in his subjects’ apartments or hotel rooms. At times he would also transform his own residences in Paris and later in Monte Carlo into sparse settings for subtle stagings. Or he used business locations, like that of jeweler Gianni Bulgari, or the editing studio of director Francis Ford Coppola, as well as public spaces, such as the forest that served as a backdrop for actor Anthony Hopkins. His subjects play themselves in a way, or a chosen role. At times they gaze in moving contemplation, found in the portrait of photographer Bill Brandt, or surprise us with a provocative gesture like that of musician Malcolm McLaren, who rips open his shirt, offering up his naked torso to the photographer. Equally interesting are the interactions in Newton’s double and group portraits: often they are of couples, like Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall, or David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini, presented in intimate poses. Here as well, Newton achieves an incomparable combination of voyeurism and exhibitionism.

.png)

© Helmut Newton. Sigourney Weaver, Los Angeles, 1983

© Helmut Newton. US Vogue, Monaco, 1996

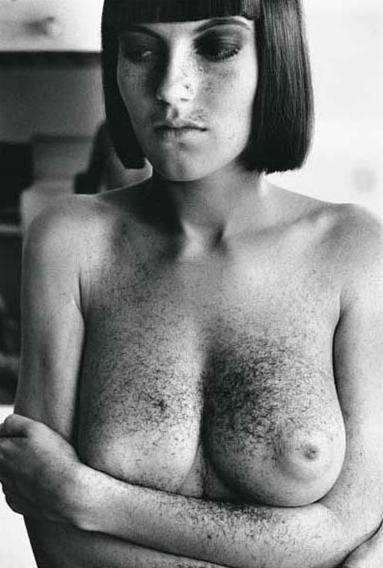

This spirit continues into the foundation’s central exhibition space, which is dedicated to Newton’s nude photography. For the first time we encounter later Big Nudes, which he shot in the 1990s in Monte Carlo, Paris, and Nice, the “Walking Women” triptych, as well as the renowned photograph “Arielle after a Haircut” – all of which are iconic photographs at the juncture of fashion and nude photography. In 1981 Newton began his legendary “Naked and Dressed” series, at first en plein air in Brescia for Italian Vogue, and later in the Parisian studio of the fashion magazine’s French edition. Newton had already shot several nudes there, interestingly in an editorial context, which were then printed in the magazine alongside the fashion shots. The models’ movements in the minimalistic studio setting – first clothed and then naked – was singular. Often the women are pictured alone and in full length, sometimes presented in life-size dimensions. Rarely do they appear in pairs or in larger groups. His nude torsos are an exception, and all of them are unusual encounters, for example when “Miss Livingston” stands at her pool in California, looking confidently straight at the viewer. It is in this way that Newton inevitably makes us voyeurs.

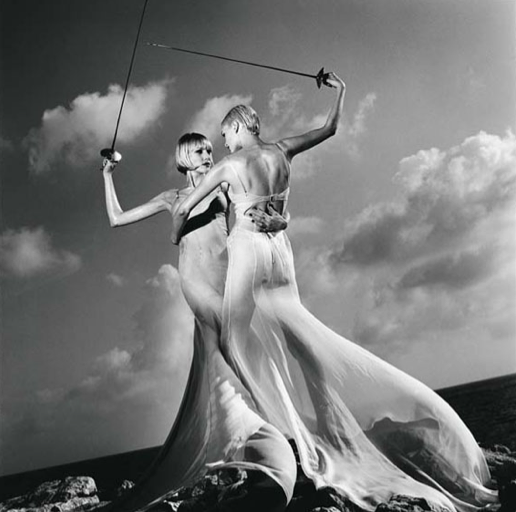

In his fashion photography, on display in the last exhibition room, we discover erotically charged scenarios where young, self-confident women star in the leading roles. Posed on the Canal Grande in Venice, a mountain on Hawaii, or an alleyway in nocturnal Paris the models wear dresses and fur coats by famous fashion designers. These photographs not only pair elegance with seduction but also reflect and comment on the shifting role of women in western society at the time. They were mostly commissioned and first published by fashion magazines, before later being presented in Newton’s exhibitions as enlarged photographic prints. Both timeless and contemporary, the fashion photography of Newton and other photographers started to be shown in museums and published in books in the 1980s. This shift in media context, between original intention and later use should be considered in today’s reception of his works. Newton’s motifs function perfectly in both genres.

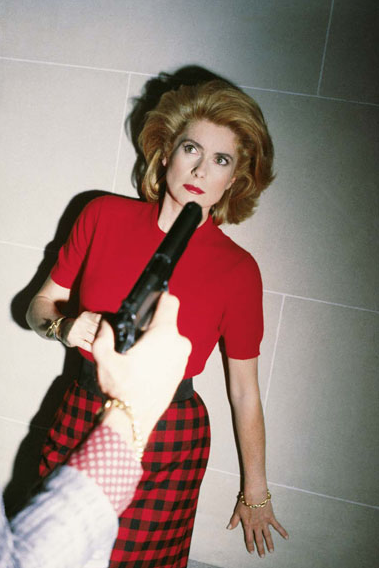

© Helmut Newton. Catherine Deneuve for a photo-essay

in Nouvel Observateur, Paris, 1983

Finally, in June’s Room, visitors can experience a selection of enlarged contact sheets featuring various constellations of figures, offering a unique view into Newton’s work process. Some include the entire photo shoot, allowing us to follow the photographer’s decision-making process in selecting the final picture-worthy shot.

Regardless of the genre in which he worked, Helmut Newton, as we witness in documentary films by his wife, only gave his models a few concrete directions before triggering the camera. This was always stocked with analogue film material, and in most cases, the negative corresponded to the print. Newton determined the motif during the working process and not after the fact with lab assistants in the darkroom. This is remarkable when compared to today’s work methods, where no printed portraits, fashion, nudes or advertising photographs are without some degree of digital image processing. The 1970s and 1980s, during which most of this exhibit’s images were shot and printed, can now be described as a classic period in photography. And as we can see here, many of Newton’s images are iconic of the times.

© Helmut Newton. Arielle after a haircut, Paris, 1982