These vignettes reflect a broader reality. There is no easy or entirely consistent way to talk about poverty in the United States. Statistics give the illusion of a neat narrative. There are more than 46 million Americans living in poverty, a full 15 percent of the population, which is the highest percentage since the early 1990s, and the largest raw number since the U.S. Census Bureau began keeping track in 1959—a reflection, many believe, not just of recent recession but also of long-term trends in income inequality and economic instability. Yet look behind the numbers, and, contrary to what you might expect, you’ll find no single archetype of the American poor. The poor are low-wage workers, lone mothers, disabled veterans, the formerly incarcerated, the mentally ill, and people reeling from lost jobs and natural disaster. They are immigrants, the elderly, the addicted, the undereducated, and the fallen middle class. They are black and Hispanic and Native American, but, more than anything else, they are white. They live in cities, suburbs, and small towns, sometimes in segregated high-poverty neighborhoods and sometimes just down the street from the solidly middle class. There is no single cause of their poverty, and there is certainly no singular solution.

Still, their tales, wrapped in a heart-wrenching mix of anguish and optimism, produce common refrains. Those refrains are the larger story told in American Realities.

Part of that larger story is how poverty in the United States can look quite different from that of the developing world. Poor Americans often own televisions and microwave ovens, even the houses in which they live. That disconnect arises partly from the unstable nature of living at the bottom of the U.S. income distribution: Americans move in and out of poverty often. During 2009 and 2010, an entire 28% of the population spent at least two months under the U.S. Census Bureau’s “poverty line” ––which is meant to indicate how much income is necessary for a family to meet basic needs—and yet only 4.8% of Americans spent the whole 24-month period below the threshold. Cycling in and out of poverty, having money for a car payment one month and then not enough for food the next, is the dark side of American economic mobility. Anxiety about losing what has been gained permeates conversations with the U.S. poor.

But there is a greater truth at play, too. A core aspect of being poor in a rich nation is struggling to stay connected to the social and economic mainstream. Writing in the 18th century, political economist Adam Smith remarked that for a day laborer to appear in public without a linen shirt would denote a “disgraceful degree of poverty,” even though ancient Greeks and Romans managed just fine without such luxury. That matches up with how people intuitively understand poverty. Since the 1950s, the polling firm Gallup has asked Americans how much money a family needs to get by. As living standards have risen, so have the estimates. In other words, as average income increases, so does the amount of money people think is necessary to meet basic needs, a perception that suggests part of being non-poor is participating in society in a dignified way—being able to join in conversations about popular TV shows and to follow friends online.

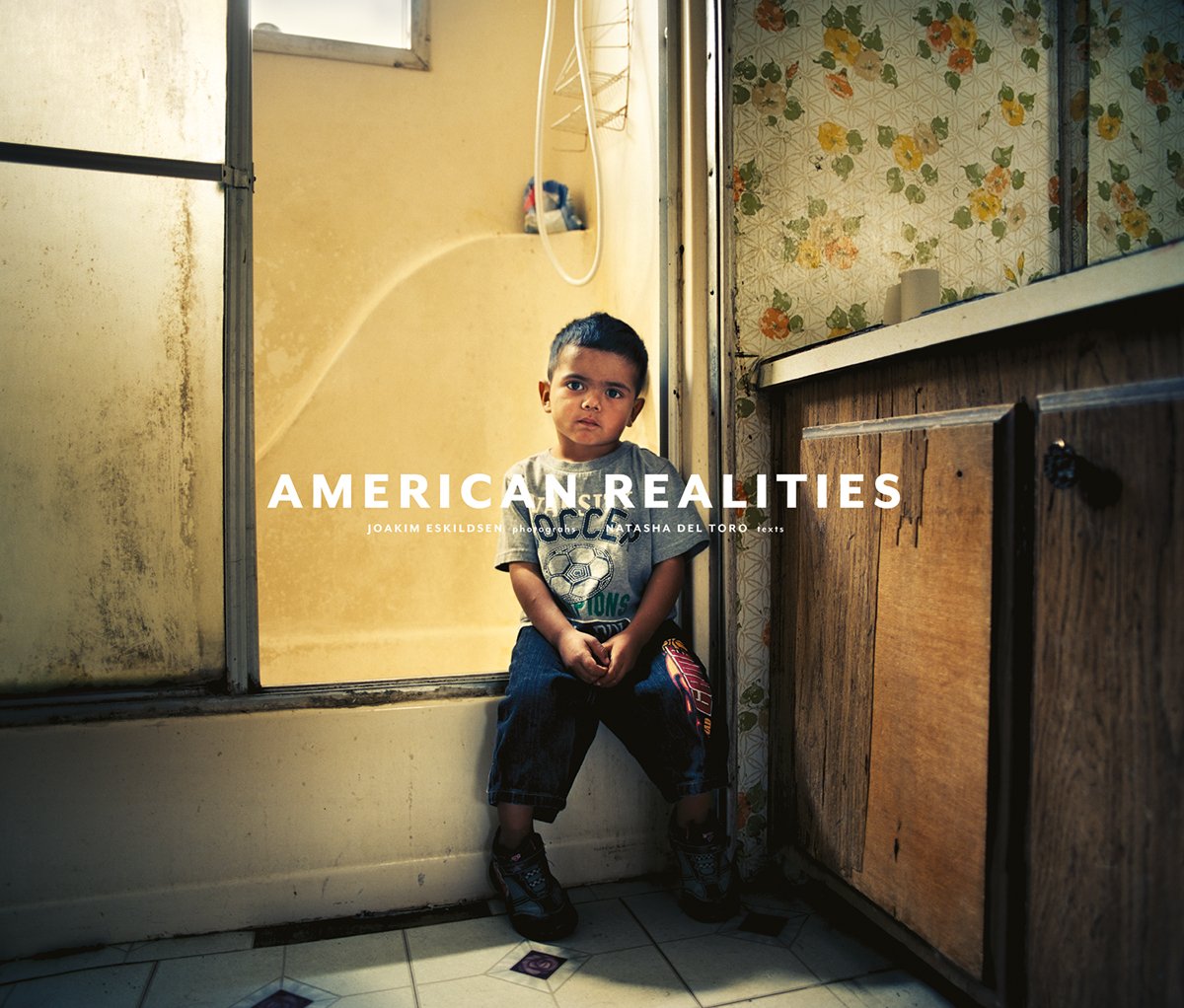

That is not to say the United States lacks true deprivation. This book is a testament to that. In Georgia and California, families live in tent cities, unable to afford permanent shelter. In Louisiana, a man whose grocery store was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina goes to jail for stealing food to feed his family. In South Dakota, a woman who works as a dishwasher stands with her grandchildren in front of their burnt-out trailer —a common scene in a place where affordable housing is all too often condemned, and clearly dangerous. People talk about chronic health problems and unaffordable insurance. They describe the fear of living in high-crime neighborhoods, the stress of being out of work for months at a time, and the turbulence caused by events like a car breaking down—a common enough problem that can prove debilitating to those who can’t fall back on a savings account or the goodwill of an employer who provides personal days. They talk about drug use, physical abuse, and of having family members they could turn to if they just weren’t so ashamed of having failed in a country where people believe—foolishly or not—that anyone can make it on his own.

It is difficult to look at these photographs and not ask, “How can this be?” and “What can be done?” Ideological tropes are easy to come by. If only the poor worked more, if only jobs paid a living wage, if only people stopped spending money so frivolously, if only the government designed a social safety net without so many holes. But one-stop solutions belie the complexity and heterogeneity of poverty in America. For certain people, not having enough income is about the precariousness of the U.S. labor market. For others, it is about a life-derailing event like a disability or the death of a spouse. For others still, the story is one of living in a place with a historically rooted tangle of pathologies like racism, alcoholism, and low levels of education. While most Americans bounce in and out of poverty, often repeatedly, a significant minority remains stuck there for years on end, indicating a totally different set of social and economic dynamics. And for a small group, falling below the poverty line doesn’t feel like a problem at all. Despite an ascetic lifestyle, some of the American poor feel perfectly free to pursue their goals, such as lives devoted to art or spirituality.

The human mind understands the world by grouping disparate items into categories, and in conversations about American poverty, that tendency often leads to talk of the “deserving” versus the “underserving” poor—those, like the disabled, who can’t help themselves, and those, like the unemployed, who could if perhaps they only tried harder. Indeed, since the beginning of the United States, and for far longer in Europe, there has been a tension in modern society between wanting to alleviate the suffering of the poor and wanting to force them to be self-sufficient.

What this book shows us is that such a simply framed trade-off masks the rich detail of the ground-level view. Take time to walk among the poor, and soon pitying them will make no more sense than vilifying them. If poverty in America is a contradiction on a macro level—how can a rich country have so many poor?—then it is truly one in the lives of the people living it. Listen to the poor in America, and you will hear tales of trauma and desperation—but you will also recognize a quintessentially American optimism. Grown men will cry in front of you, but then they will talk about their hopefulness. All around, you will sense depression and angst, but then you will hear well-worn lessons of not giving up, of staying positive, of continuing to fight, of keeping faith. The very people for whom the system has failed, the ones who are most disillusioned with it, will vigorously defend it.

Whether or not it is always possible to work one’s way up in the United States, whether or not the American dream holds true, the idea of it clearly reverberates, for even the poor believe that someday things are sure to get better.

Barbara Kiviat, a former staff writer at Time magazine, is pursuing a Ph.D. in sociology and social policy at Harvard University.