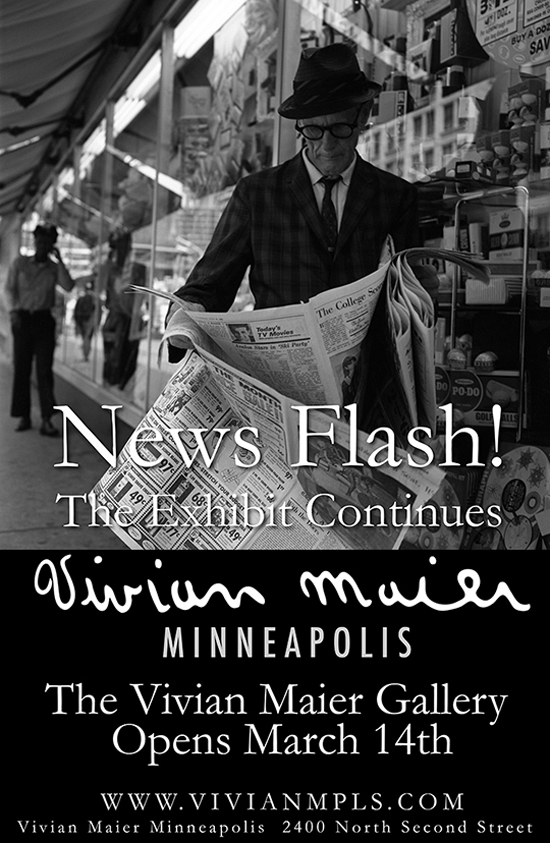

MPLS photo center 2400 North Second Street MN55411 Minneapolis États-Unis

From Unknown Amateur to Celebrated Artist, an Essay by Elizabeth K. Whiting

“That rare case of a genuine undiscovered artist, she left behind a huge trove of pictures that rank her with the great American midcentury street photographers. The best pictures bring to life a fantastic swath of history that now needs to be rewritten to include her.”

—Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times Magazine, 16 February 2012

Amateur photographer Vivian Maier strolled the streets and neighborhoods of Chicago, and with her Rolleiflex camera she photographed people of all ages, races, social, and economic backgrounds. With the eye of an artist, she captured the poetry of the streets and the complexities of her urban environment in her remarkable black-and-white photographs. Maier made an extraordinary and sympathetic portrait of Chicago and its people in the 1950s and 60s and is posthumously earning a reputation as one of America’s great art photographers.

Vivian Maier saw the world—and ultimately experienced life—through her camera. This self-taught photographer used her Rolleiflex like a “passport” to access and move easily and unobtrusively among the inhabitants of Chicago and its environs. Elusive, secretive, and described by others who knew her as eccentric and a mystery, she photographed people and commonly overlooked moments. Working unnoticed, Maier observed the world with a keen eye revealing the private moments of her subjects. Her photographer’s eye made visible the art she saw in the city, and her photographs celebrate the creative spirit that flourished within her. Vivian Maier was Chicago’s invisible street poet. And as a poet, Maier captured and created lyrical images that reflect the theatre of the city streets and the unique spirit of the time.

Born in New York City in 1926, Vivian Maier spent part of her early childhood in France returning to New York in the late 1930s. In 1956, she settled in Chicago where she remained until her death in 2009. She worked her adult life as a nanny and caregiver to a series of North Shore families and devoted her free time and money to her passion: photography. She began photographing her world first in France (1940s), then New York (early 1950s), and finally Chicago and the North Shore suburbs (1956 to the mid-1970s). Her camera was always with her, she photographed nearly every day. She enthusiastically pursued her passion in between and even during her duties as a nanny, photographing her young charges and their friends at play, experiencing and exploring their world.

Vivian Maier photographed the endless procession of Chicago’s inhabitants and preserved their urban vignettes in medium format, square black-and-white images. In this parade of humanity, Maier’s photographs also subtly allude to the underlying anxieties and the growing alienation and gap between the rich and the poor; and the clash between the traditions of the establishment and elderly, and the racial tensions that permeated postwar America. In contrast to the comfort of postwar America that Maier often photographed, her images also reveal the complicated times of the tumultuous 1950s and 60s. The growing youth- and counter- culture and America’s unease during the McCarthy-Vietnam-Civil Rights eras are poignantly captured and contrasted with Maier’s everyday images like Girls Wading in Lake Michigan, Boy Holding Ears, Mother and Children in Car, and Man Standing in Doorway.

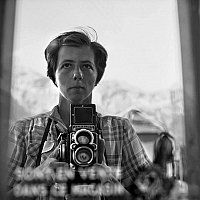

Maier’s quirky nature—characterized by a propensity to wear odd clothes and hats as well as men’s shoes—also translated to her unconventional camera choice. Maier consistently photographed with a Rolleiflex camera. A medium format camera encourages a slower, more deliberate way of making an image and fosters a more composed aesthetic. The Rolleiflex was a idiosyncratic choice, especially during the widespread use in the 1950s and 60s of the fast, modern, and easy to use 35mm camera and the popularity of the snapshot aesthetic being masterfully practiced by such artists as Robert Frank, William Klein, Saul Leiter, Garry Winogrand, and Joel Meyerowitz.

While Maier occasionally photographed with a 35mm camera, she clearly preferred the Rolleiflex and its 2 ¼-inch square negative—Maier would hold her Rolleiflex camera at waist-level and stare down at the camera’s ground glass to see and frame a scene squarely. The classic pyramid compositions and frontality of Man Leaning on a Ladder, Man Drinking and Smoking, Man Standing with Newspapers, Man Sitting on Car Bumper, and the masterful Woman with Floral Hat, capture Maier’s more formal aesthetic, her way of ordering the disorder and engaging with disconnected strangers she encountered in the city.

Diane Arbus, Maier’s contemporary, also favored a medium format camera that produced square negatives. While their photographic missions differ, their commitment to the square format at a time when the 35mm rectangle dominated reflects the unique vision of both women artists. But while Arbus employed the square composition to enhance the emotional intensity of her subjects, Maier keeps her distance. In fact, many of Maier’s best works depict people taken from behind—Man in Hat from Behind, Hands Behind Back, Holding Hands, Woman with Fox Fur, andWoman in Sweater from Behind. This method of viewing the world is enhanced by the usage of the Rolleiflex, a camera where the operator looks down into the camera held at waist level rather than looking directly at the subject with a camera held up to the photographer’s eye. This non-confrontational working method, along with being a woman, made Maier non-threatening allowing her to work unnoticed. Because people did not always notice her, she was able to capture and contain the details that expose their humanity revealing small telling gestures and disclosing physical attitudes normally hidden.

When Maier was not photographing the cavalcade of urban street characters, she photographed herself. The enormous cache of Vivian Maier photographs and negatives reveal a plethora of self-portraits. It is when the artist turns the camera on herself that she depicts a more private and internal narrative creating some of her most compelling, haunting, and puzzling photographs. A mixture of aesthetic cunning and emotional reticence conveys the enigmatic quality of self-reflection and anonymity, which haunts much of Maier’s work. Each self-portrait is carefully constructed and artfully composed, but instead of revealing her identity Vivian Maier remains unknowable, a mystery, a weird and wonderful secret.

Vivian Maier seemed to relish being an observer on the edges and working in anonymity. Over the course of her adult life, Maier made more than 120,000 images. She printed only a fraction of her enormous output—most of which remained as negatives or even undeveloped film, unseen even by her in their printed form. Despite all that she made, she apparently did not share her photographs with others, virtually no one saw them. She did not pursue awareness or acceptance from the art community and did not seek celebrity or fame.

Towards the end of her life, Vivian Maier could no longer afford to pay for the storage lockers that held her photographs, negatives, personal papers, and other belongings. Like buried treasure, her prodigious body of work remained hidden and unknown. Had it not been for the discovery of her work in 2007, followed by its cataloguing and careful promotion, Maier would have died in obscurity and her art destroyed or lost forever. As a matter of course in his business, Roger Gunderson of RPN Sales and Auction bought the five abandoned storage lockers forfeited by Maier—unaware of the potential treasure inside—and then auctioned off the contents to a group of half a dozen or so unaware buyers of what their purchased lots really held.

The posthumous treatment of an artist’s work can be a thorny and controversial effort. Managing and advancing Vivian Maier’s creative process has sparked questions and debate. When the creator has passed on and there are no explicit instructions or guidelines for interpreting and presenting their creative output—what does one do with undeveloped film or unprinted negatives? How does one determine image selections? What images would Vivian Maier have chosen? Most likely, she would not have wanted fame or attention, as she did not seek it in her time. To do nothing with her newfound photographs, however, would be unfortunate and a loss to the art world.

It is poignant to note that when Maier identified herself in legal documents, it was simply as a child nurse. Today, Vivian Maier is posthumously recognized and celebrated for what she is: an Artist.

The Vivian Maier phenomenon begins with the fortuitous discovery and recovery of her work. Her astonishing photographs and dramatic story have captured the public’s imagination. The next chapter in the Vivian Maier narrative will be for scholars and museums to consider and establish her role in the history of American photography. Her photographs and creative output will prove indelible, and surely she will be recognized as one of the artists whose vision helped define American photography in the mid-twentieth century.