Lion & Wildebeest © Nick Brandt

A.galerie 12 rue léonce Reynaud 75116 Paris France

Au même moment sortira le livre « Across the Ravaged Land » - Edité par Abrams – 38cm x 33cm – 120 pages

« Ce livre est dédié aux milliards d’animaux, dans le passé, le présent et le futur, qui sont morts sans raison par la main de l’homme. »

Across the Ravaged Land est le 3ème et dernier volume de la trilogie de Nick Brandt expliquant en photographies la disparition d’un écosystème et l’extermination des animaux sauvages d’Afrique de l’est.

1er livre : “On this Earth” (2005)

2ème livre : “A shadow falls” (2009)

3ème livre : “Across the Ravaged Land” (2013)

Les trois titres à la suite se lisent : On this Earth, A shadow falls Across the ravaged land... Sur cette terre, une ombre s’abat sur un monde ravagé ... !

La nouvelle série de photographies de Nick Brandt offre une version plus sombre d’un monde toujours empreint d’une grande beauté mais qui se teinte petit à petit de noirceur et qui disparait tragiquement par la main de l’homme.

Ce nouvel opus de Brandt est le point culminant de plus de 10 ans de travail durant lesquels la population animale à l’instar des éléphants, des lions et autres grands mammifères n’a fait que décroitre précipitamment.

Durant toutes ces années, la précision de l’œil de Nick Brandt et son attachement pour ses sujets n’ont fait que s’accentuer. Ses portraits d’animaux résonnent d’une simple idée : toutes ces créatures sont capables de ressentir, d’avoir des sentiments, elles ne sont finalement pas très différentes de nous et ont, au même titre que tout être humain, le droit de vivre.

En plus de ses portraits d’animaux précis et puissants, Nick Brandt explore cette fois-ci de nouveaux thèmes : des êtres humains apparaissent enfin dans son travail pour la première fois sous forme de rangers dont le rôle est de protéger cet écosystème. Dans cette nouvelle série apparaissent également pour la première fois quelques cadavres,

des hyènes, des serpents, des oiseaux « calcifiés » et des trophées d’animaux regardant cette terre qui était autrefois la leur.

A travers toutes ses images empreintes de gravité, Brandt dresse le portrait d'une Afrique mythique qui se bat tragiquement contre des forces implacables. Dans quelques années, en regardant ces clichés impressionnants, nous nous demanderons pourquoi l'humanité n'a pas fait davantage pour préserver ce coin de paradis terrestre.

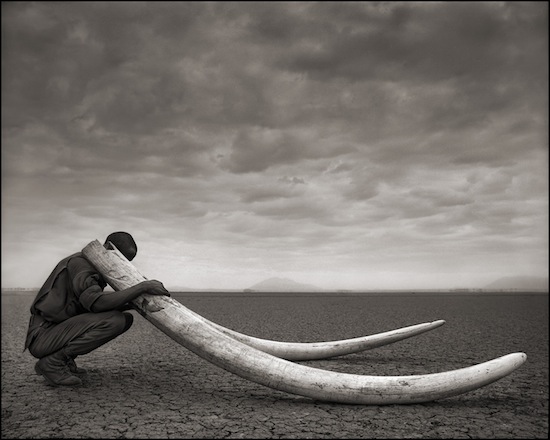

Ranger with Tusks of killed Elephant © Nick Brandt

Nick Brandt

Nick Brandt est né et a grandi à Londres où il a étudié le cinéma et la peinture dans la célèbre école des arts de St Martins. Il vit actuellement à Malibu en Californie.

En 1992, il décide de s’installer aux Etats-Unis où il va très rapidement réaliser des clips-vidéos pour des superstars telles que Michael Jackson (« Earth Song », « Stranger in Moscow »), Moby ou Jewel. C’est en allant tourner en Afrique avec Michaël Jackson qu’il décida d’arrêter de filmer pour se consacrer à la photographie & à la nature. En 2000, il débute en Afrique de l’Est sa carrière de photographe et créé le style si particulier qui le caractérise. Peu de photographes ont réussi à photographier le monde animal de la sorte. Ses images n’ont rien à voir avec un reportage de National Géographic, elles entrent dans le cercle fermé des « Beaux Arts ». « Je veux faire des photographies qui transcendent le genre très documentaire de la photo animalière ». Le premier ouvrage de Nick Brandt sur les animaux, « On This Earth » a été publié en Octobre 2005 par Chronicle Books, avec des avant-propos de Jane Goodall et Alice Sebold (Auteur de « The Lovely Bones »). Et les talents de photographe de Nick Brandt furent salués unanimement par la critique. Selon le Times, "la faune sauvage africaine ne nous est jamais apparue aussi majestueuse et mystérieuse que dans les photographies pleines de gravité de Brandt". American Photo écrivait : "En associant de splendides arrière-plans naturels à une approche de portraitiste animalier, Brandt nous montre non seulement la beauté téméraire d'une vie sauvage africaine en voie de disparition, mais aussi l'humanité de ses créatures. Une étrange impression d'intimité se dégage de ces photos". Enfin, Black & White Magazine qualifiait les images de Brandt de "belles à fendre le coeur".

Nick Brandt utilise avec talent son amour de la photographie comme support pour exprimer la vérité. « Au delà de l’utilisation de procédés techniques particuliers, il y a une chose que j’essaye de faire pendant que je shoote qui, à mon avis, fait la différence: je suis très près de ces animaux extrêmement sauvages, à quelques mètres parfois. Je n’utilise jamais de grand téléobjectif. C’est parce que je veux voir sur mes photos le plus de ciel et de paysage possible que je me rapproche, afin d’avoir l’animal dans son réel environnement. Ainsi, la photographie concerne autant l’animal que son lieu de vie. En étant aussi près d’eux, je finis par avoir une certaine intimité, une connivence avec l’animal qui me fait face. J’ai même parfois l’impression qu’ils sont presque en train de prendre la pause comme dans un studio photo ».

Pourquoi choisit-il les animaux d’Afrique et en particulier ceux d’Afrique de l’est ? « Car il y a quelque chose de profondément iconique, mythique, de mythologique même, avec les animaux d’Afrique de l’Est, contrairement aux animaux d’Arctique ou d’Amérique du Sud. Il y a aussi une très grande émotion qui se dégage des plaines d’Afrique, ces grands espaces verts qui s’étalent sous vos yeux, ponctués par la perfection graphique des acacias. Je pense sans honte que mes images sont idylliques et romantiques, et représentent une certaine vision d’une Afrique enchantée. Elles sont mon élégie à un monde qui est tragiquement en train de disparaître ».

Depuis 2004, Nick Brandt a exposé en solo dans les plus grandes galeries de Londres, Berlin, Hambourg, New York, Los Angeles, Santa Fe, Sydney, Melbourne, San Francisco et à la A.galerie à Paris.

En 2010 il a crée the Big Life Foundation pour aider à la préservation des écosystèmes du Kenya et de la Tanzanie, en signe de son engagement profond pour la conservation des espèces.

Lion Roar © Nick Brandt

ACROSS THE RAVAGED LAND

Take a look at the elephant in the photo opposite. His name is Igor (as named at birth by Cynthia Moss of Amboseli Elephant Research). For forty-nine years, he wandered the plains and woodlands of the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa. A gentle soul like most elephants, he was so relaxed that in 2007, he allowed me to come within a few feet of him to take his portrait.

Two years later, in October 2009, it was perhaps this level of trust that allowed poachers to get close enough to kill him and hack out the tusks from his face.

This book, Across The Ravaged Land, is the final book in the trilogy that I began in late 2000. Being something of a natural pessimist (always tempting to actually just say “realist”), I always felt that I was potentially making a final testament, an elegy, to the extraordinary natural world of East Africa, and the wild creatures that inhabited it. Back then, in my first book, On This Earth, I photographed what I saw as something of a paradise, an Eden. And it was, compared to what is happening today in 2013. But even thirteen years ago, my pessimistic mind did not conceive that things would turn this bad, this quickly.

As I write, there is a continent-wide apocalypse of all animal life now occurring across Africa. When you fly over such a vast continent with so much wilderness, it’s hard to imagine that there’s not enough room for both animal and man. But between an insatiable demand for animal parts and natural resources from other countries, and a sky-rocketing human population, the animals are being relentlessly squeezed out and hunted down. There is no park or reserve big enough for the animals to live out their lives safely.

The statistics are finally, belatedly, starting to become known, and they need repeating:

Every year, an estimated 30-35,000 elephants a year are being slaughtered across Africa. That’s 10 percent of the elephant population every year.

Fed by the massively increased demand from China and the Far East, ivory prices have soared from $200 a pound in 2004 to more than $2000 a pound in 2013. China’s population is 1.3 billion and counting, and with 80% of its fast-

growing middle class keen to buy ivory in some form, its price will only keep spiraling upwards. (It barely merits stating the obvious: that ivory is never more beautiful than when thrusting magnificently out of the face of an elephant).

As for rhino horn, it’s now more expensive than gold dust in the Far East, as the last rhino are gunned down to provide phoney “medicine” for men with failed libidos. There are an estimated 20,000 lions left in Africa today, a 75 percent drop in only twenty years. Most of this decline is due to conflict with the fast growing human population. But increasingly, lions are killed for body parts like claws, bones and teeth, again for the Asian market, now that tigers are too hard to procure. It has become so bad that there are next to no lions left outside the parks and reserves.

Viewing the steep downward slope on the graphs, it means this: at the current rate of slaughter, there will be no elephants, no lions, no cheetahs left in the vast expanse of the African continent within fifteen years.

The only place you will be able to see them is in the sad, drab confines of zoos. Or in fenced areas that constitute barely more than a glorified zoo. Once again, man is on the path to systematically exterminating entire species of his fellow creatures in the natural world. Will humanity learn and change as a result? Based on history, the despairing answer is no.

It all sounds fairly bleak, and much of the future inevitably will be. But there is a “however...” There has to be a “however...”

But we have to be prepared and willing to engage in the most almighty fight for it....

In July 2010, I returned for the first time in two years to the Amboseli ecosystem, a two million-acre area bordering Kenya and Tanzania in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. Over the previous six years, I had spent many months photographing the elephants that inhabit this region. As a result, I had been fortunate to come to know some of these amazing creatures intimately.

Whilst there in 2010, I learned about the killing the year before not only of Igor, but others as well, like Marianna, the matriarch purposefully leading her herd in the photograph below.

Day after day, we tried to approach what had once been some of the most relaxed of elephant herds, elephants that in the past had quietly made their daily journey to the swamps, moving past and around our vehicle without a care in the wæorld. But this time, when we approached to within half a mile, they would run in terrified panic. Meanwhile, gunshots were being reported from the direction that the elephants came, near the Tanzanian border.

We tried reporting what we’d seen, but nothing was done, nothing happened. The Kenya Wildlife Service was (and still is) underfunded, and the few NGOs in the area had insufficient funds and infrastructure to make much of a difference. On the Tanzanian side, there was no one at all engaged in protection or conservation. And this was here in the Amboseli ecosystem, one of the most important and famous in Africa, with the most spectacular remaining population of elephants to be seen in East Africa.

Over the coming weeks, there was a lot of bad news. Just six weeks after I took the photo below of Winston, this thirty-year-old elephant, barely into his prime, with half his life ahead of him, was shot by poachers over the border in Tanzania. Wounded, he made it back over to Kenya, where he died. He also had his tusks sawn out of his face with a power saw by the poachers. (And you won’t want to read this, but many are the elephants who are still alive when the chainsaw, or ax, starts hacking the ivory out of their faces).

Over the next couple of months, the roll call of big bull elephants killed by poachers came thick and fast: Goliath, Sheik Zahad, Keyhole, Magna, and more. It wasn't just a case of IF a big-tusked elephant was going to get killed, but WHEN.

At first I thought the poachers would just target the elephants with big tusks. But elephants with tusks barely more than broken stumps were being killed by poachers. Which meant that really, no elephant was safe any more.

The killing was also escalating for all the wild animals of the area. The plains animals were getting slaughtered; giraffes here in the region were being killed at a faster rate for bush meat; there were even contracts out on zebras, as their skins became the latest fad in Asia.

As I saw the destruction unfolding with almost no real or meaningful protection, I thought that I can’t just stay frustrated, depressed and powerless. It’s no good being angry and passive. It’s much better to be angry and ACTIVE.

And so, to my own complete surprise, I co-founded Big Life Foundation in late 2010, made possible by an incredibly generous donation from one of the best collectors of my photographs. Partnering with the highly regarded conservationist Richard Bonham, we set our sights on the Amboseli ecosystem as our pilot project: a nearly two- million acre area stretching across the Kenya/Tanzania border.

A little over two years later, Big Life has 280 rangers, 24 ranger outposts, 15 patrol vehicles, 2 planes for aerial monitoring, 3 tracker dogs, and a vast informer network across the whole region. It’s the only organization in East Africa with co-ordinated cross-border anti-poaching operations.

With this infrastructure in place, as of April 2013, the Big Life teams have achieved a dramatic reduction in poaching of all animals in the region. None of this could have happened without one critical element.

With animals constantly moving far beyond park boundaries into unprotected areas ever more populated by humans, the only future for conservation of animals in the wild is working closely with the local communities. Effective conservation is dead in the water without community collaboration. This is at the heart of Big Life’s philosophy. The people support conservation, conservation supports them.

In parts of the world such as this, very poor but rich in natural wonders, ecotourism is the only truly significant source of long-term economic benefit. Take away the animals, and there’s almost nothing of economic value left. The land can only support so much herding, and even less farming. And those meager resources will only become more unsustainable and precarious over time, as climate change kicks in and brutal droughts occur more frequently.

When you’re trying to protect close to two million acres, with the best will in the world, 280 rangers and 15 vehicles are only going to get you so far. That’s where the support of the community is essential. Big Life’s expansive network of community informers is one of the main reasons why the rangers now apprehend poachers most times that they kill. Every one of those rangers lives locally, and with families whose wellbeing is tied to their success, and the wealth of the region increasingly understood by local people to be tied to the health of the ecosystem, so each ranger has his own small network of other eyes and ears. Given the size of the area, I find it quite amazing, and very encouraging, just how often information does come through to the teams about poachers operating in the area. And on the poacher grapevine, it is now known that you run a big risk of being arrested if you attempt to kill in the Big Life- protected areas.

But the aim of Big Life has always been to do much more than just catch poachers. Its aim is to protect the entire ecosystem, both in the short and long term. Loss of wildlife habitat, the expansion of human settlement due to population pressure, and the resultant animals killed during raids on farmers’ crops or in retaliation for attacks on livestock - all add to the toll of lost wildlife. And all, in one way or another, we attempt to address.

Meanwhile, however, the destruction of wildlife continues, escalating and out of control, in the areas beyond where the Big Life teams operate. This is why this year, 2013, we began to extend operations into the Tarangire/Manyara area of Northern Tanzania, where large numbers of animals, from giraffes to zebras, were being gunned down for the bush meat markets of Arusha and beyond.

However, I don’t want this to turn into an extended pitch for what Big Life Foundation is doing. If you’re interested, you can discover more at Big Life’s website. But if you’ve made it this far, perhaps that means you might join the fray.

Unfortunately, we’ve reached a point where a series of terrible choices have to be made: what we can still try and save, and what we have no choice but to painfully, reluctantly sacrifice.

All across the African continent, there are entire populations of elephants and other animals now being wiped out. The list is long: animal populations in Chad, Central African Republic, Mozambique, Congo, large parts of Tanzania, and on and on. Tragically for many of the ecosystems in these places, any conservation group would face an overwhelming struggle to be effective - for lack of government support or community collaboration, for lack of money, for lack of firepower against the rebel militia groups that sweep in to murder en masse, financing weapons purchases with their bloody bounties of ivory. In fact, as I’m writing this, I’ve just read a news report about 86 elephants killed in the last week in Chad, including 33 pregnant females. And no one there to stop it for all these exact reasons.

So until sufficient national and international pressure is exerted to implement truly meaningful bans on the worldwide trade in animal parts, we will have to continue to choose which battles we stand a chance of winning, and those we know that we cannot.

The photograph above (that can be seen full size on p.xx), shows twenty-two of the Big Life rangers holding tusks of elephants killed by men within the Amboseli/Tsavo Ecosystem in the years 2004-2009. The photo was taken to echo the earlier photograph, Elephants Walking Through Grass, reproduced a few pages back.

Corporal Kitanki - at the front, and with one of the best track records of capturing poachers - is holding tusks that each weigh in excess of 120 pounds. These same tusks are supported on the shoulders of another Big Life ranger, Corporal Pepete, in the photograph on the cover of the book.

Those two gargantuan tusks, that bounty, would fetch close to half a million dollars in China today. However, as I look at those tusks in the photo today, I’m not thinking of that.

I’m looking at them thinking that actually, I find it hard to visualize the living elephant that possessed them. I’ve never seen elephants with tusks anything like that size, and now, I never will. They are all gone, dead, mostly killed by man. Even with one part of each tusk embedded in his skull, this elephant would still surely have had to lift his monumental head to prevent them from dragging like excavators through the earth.

On October 27 2012, I took the photo above, of Qumquat, one of Amboseli’s most famous matriarchs, and her family. Beyond are two of her daughters, Qantina and Quaye, bearing smaller tusks. You can see that I was just a few feet from the family, so trusting, so relaxed. Such easy pickings for poachers with a mind to murder for profit. Sure enough, this was to be their last afternoon alive.

Twenty-four hours after this photograph was taken, Qumquat, Qantina and Quaye were gunned down by one of Amboseli’s most notorious poachers (whom the Big Life rangers subsequently apprehended). As for the three youngest, two are missing, the younger almost certainly dead now. Only the youngest calf is alive, his new home the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Orphanage in Nairobi.

This is the kind of collateral damage that the poachers cause: abandoned, traumatized calves that cannot survive once their mothers are gone.

Qumquat was a wonderful matriarch, who successfully led her herd for many years. But in one hellish afternoon, three generations of her family were exterminated.

Meanwhile, there are thousands of other Qumquats and sons and daughters still across much of Africa, many of whom will inevitably meet a similar fate.

Whether this kind of senseless destruction motivates you to donate to Big Life, or another group working to protect the animals or environment here or elsewhere on the planet, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that, cliched as it sounds, if you care, get involved. Don’t be angry and passive. Be angry and active.

This book marks the end of the trilogy - On This Earth, A Shadow Falls, Across The Ravaged Land - that began in paradise, and ends in a much more somber place. I took portraits of the animals in these books in an attempt to capture these animals as sentient creatures not so different from us. I have sought to photograph them not in action, but simply in a state of BEING. Let us continue to let them be.

.jpg)

Calcified Fish Eagle © Nick Brandt

I AM THE WALRUS

The animals came first. Not the photography, but the animals.

Or to elaborate, my love of animals came first. Photography was merely the best medium to convey my love of, and fascination with them.

I first visited East Africa in 1995 whilst directing “Earth Song”, a music video for Michael Jackson. I fell in love with the place and with the animals. Thatʼs not very surprising – it has a similar effect on many people. But that experience shifted my focus in terms of what I wanted to say about the world. So I spent the next few years trying to find feature film projects that dealt in sophisticated ways with the subject matter of animals and the environment. But it was hard to find any story in which the money people were sufficiently interested.

Directing is a frustrating business. Vast precious tracts of your life, when, in theory, you are at your most creative and energetic, are consumed with projects that ultimately never see the light of day. You’re dependent on the money people to be able to create. And even if you’re fortunate enough to finally get that money, the compromises involved can take you a long way from your original vision. For so many in the film ‘industry’, you’re living for tomorrow, not in the present, unable to simply do what you are desperate to do: CREATE.

Photography, however, allows you to just go out and create how you want, what you want, when you want. You’re answerable to no-one. You’re in control of your creative life. Joy.

So at the end of 2000, I went back to East Africa, this time to photograph. The irony is that I had chosen a subject matter - animals - over which I had no control whatsoever.

From the outset, I had a vision in mind: I wanted to create an elegy, a likely last testament to an extraordinary, beautiful natural world and its denizens that is rapidly disappearing before our eyes. I wanted to show these animals as individual spirits, sentient creatures equally as worthy of life as us.

I chose to photograph in black and white, because aside from the purely aesthetic (the compelling graphic nature of black and white imagery), it accentuates the impression of the images belonging to another much earlier time. As if these animals in the photographs are already long gone, already dead.

Photographing with film, as I have done throughout, also gives the images an air of timelessness that digital could not.

The camera of choice was, and has remained to this day, incredibly impractical for what I do: a medium format Pentax 67II with waist level viewfinder. Just 10 shots per roll, no zoom, no auto-focus, no auto metering, no motor drive, no image stabilizer lenses. In fact I only use two fixed lenses, the 35mm equivalent of a standard 50mm and a 100mm, not out of necessity, but out of choice.

In other words, everything I do seems to be perversely, masochistically designed to increase my chances of messing up and losing the maximum number of shots in the process.

In 2011, the temptation to live an easier life - both practically and emotionally – finally seduced me. Frustrated by the number of shots I was losing shooting with film, I brought a Hasselblad 60 megapixel medium format digital camera to Africa with me. I took photos side by side with my film camera. The digital camera’s images were sharper. They had more detail in both the shadows and the highlights. The digital camera made photographing very, very easy.

And I hated it. For me, the images were too clinical, too sterile, too devoid of atmosphere. Just too....perfect. In fact, had I photographed using a digital camera from the beginning, I’m not sure that I would have liked a single photograph that I had ever taken.

So as long as there is film available to buy, and airport security people that can be gently persuaded to hand check the precious vulnerable exposed rolls, I will continue to photograph with film. And I’ll continue to lose endless shots along the way. So be it.

The first two books in the trilogy were entitled On This Earth and A Shadow Falls. The title of the final book, Across The Ravaged Land", completes the sentence and the trilogy:

On This Earth, A Shadow Falls Across The Ravaged Land.

I may have had a clear vision from the outset of how and what I wanted to photograph, but with the horrifying acceleration of destruction over the last few years, I could no longer photograph an idyllic view of what I saw. Thus the title of this book.

In the past few years, every time I photographed an elephant, I wondered if this would be the last time I would see him, and photograph him, alive. Sometimes it seemed like a miracle when one of my favorite elephants, like the beautiful giant-tusked male below (and seen larger on pages xx and xx), reappeared after months of no sightings.

How could an elephant bearing tusks such as these, his great ivory treasure worth literally hundreds of thousands of dollars in China, safely move, unharmed, across a land so filled with poverty-stricken people? How is it possible that he would not be killed for them? Indeed, some of these elephants, and lions, were killed not long after I photographed them.

And this beautiful giant-tusked male may already be dead as I write, or you read this. This further sense of foreboding, this greater level of melancholy on my part, informs the way that I photograph the animals in this book as opposed to the previous two. The shadow falling over the animals and land (and therefore also us) in the second book, is now turning a somber, inky black.

As with so much in life, sooner or later, we learn to adjust to living with diminished expectations. African savannas once teeming with wild animals not that many decades ago, are now denuded to near-emptiness, and this state becomes the new norm. This was the impetus behind the photographs of the trophy heads of lion, buffalo and kudu to be found towards the end of the book : portraits of decapitated creatures, appearing alive in death, looking out over lands where once they lived and roamed in their multitudes.

But that doesn’t mean to say that I have given up hope. In the photographs of the rangers holding the tusks of elephants killed at the hands of man, yes, those elephants were killed as a result of human greed, evil and vanity, but those men are rangers employed by Big Life Foundation, empowered to protect those elephants and other animals that are still gloriously alive.

The notion of portraits of dead animals in the place where they once lived is what also drew me to photographing the creatures in the Calcified series:

I unexpectedly found the creatures - all manner of birds and bats - washed up along the shoreline of Lake Natron in Northern Tanzania. No-one knows for certain exactly how they die, but it appears that the extreme reflective nature

of the lake’s surface confuses them, and like birds crashing into plate glass windows, they crash into the lake. The water has an extremely high soda and salt content, so high that it would strip the ink off my Kodak film boxes within a few seconds. The soda and salt causes the creatures to calcify, perfectly preserved, as they dry. I took these creatures as I found them on the shoreline, and then placed them in ‘living’ positions, bringing them back to ‘life’, as it were. Reanimated, alive again in death.

Over the years, there have been many questions regarding the work I do on the photographs after scanning the negatives. Some people think that the scenes could only have been conjured up through post-production artifice. However, I have always found that with quite endless amounts of patience and luck, the natural world will eventually, unexpectedly provide you with something far better than your imagination - courtesy of Photoshop or the equivalent - could come up with.

So the fundamental integrity and content of what you see in the final image is always there on my original negatives: the animals, the landscape, the sky were all there in that place at that moment. I don't add animals or clone them. I donʼt composite in a different sky from another time and place. From that point on, using Photoshop, there are varying amounts of tonal adjustments made within the frame before the photo is complete.

However, and again this comes back to film versus digital, I have always loved the unexpected surprises that sometimes happen with film. These surprises - mysterious, indefinable, unrepeatable - are something that would never have happened with the more literal ‘perfect’ digital capture.

There are also certain effects that I can achieve with a film camera that I could never do with a digital camera. A case in point is the shifting focal planes that are evident in some photos in the previous books, such as Lion Before Storm- Sitting Profile. Those are all achieved in camera at time of shooting, using a very crude and simple low-tech technique that could never have been achieved with a digital camera or recreated in Photoshop.

Other early effects, pre-2006, are no longer used: the infra red film to heighten the sense of idyll, the aged stains from other negatives to further convey the feeling of another time. Nowadays, I look for more simplicity.

But Iʼm talking too much technique here. Itʼs not all about technique. In that regard, I have always been inspired by an unlikely source. In fact, itʼs an especially unlikely source in the context of an essay about photographing in Africa:

The inspiration is the Beatles albums from the mid-1960ʼs. Listen to those albums, like Revolver or Sgt. Peppers. Listen to the wondrous invention of songs like “A Day in The Life” or “Tomorrow Never Knows” or “I Am The Walrus”. Listen to what they created with just four tracks of analog tape. They didnʼt need ninety-six technically perfect digital recording tracks and software and a bank of computers. They simply needed imagination and emotion, determination and belief. Technique is merely the means to help convey those, not the be-all and end-all.

So with a huge thank you to the Beatles and their great producer George Martin, bring on the film, and accompanying cursing, as yet again, the film in the camera runs out just as Iʼm about to take the impossible - but always to be hoped- for - perfect shot.

DEDICATION AT FRONT OF BOOK

Dedicated to the billions of animals,

past, present and future,

that have died without reason

at the hands of man.

Photographies et vignette © Nick Brandt