I’ve only just realised how important you are (to me) 2012 © Gemma Messih

Stills Gallery 36 Gosbell Street, Paddington NSW 2021 Sydney Australie

One sunset a day just isn’t enough. In our mediated environment, where points of view outnumber eyes to view them, it seems there is no longer one nature, just an excess of human ones. Drawing together national and international artists working at the edges of photomedia, video and installation, The Big Picture considers our experience of the sublime amid the visual excess and digital fragmentation that characterise our everyday. Using an array of materials and media, from vast online image banks to dusty photo archives, time slice technology to unwanted CRT TVs, the artists in The Big Picture present an accumulation of details in order to broaden our outlook on nature. Collectively they ask, if a picture speaks a thousand words, what can a thousand pictures reveal?

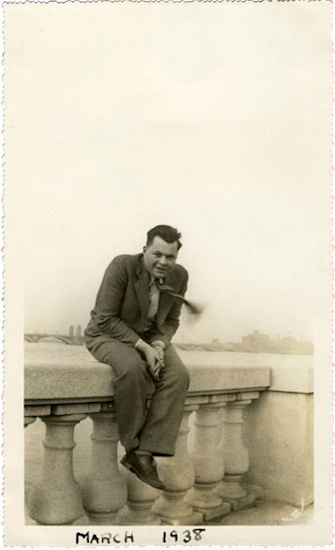

Patrick Pound’s work has the look of having been made by someone who has set out to try and explain the world and who, having failed, has been reduced to collecting it. In Portrait of the wind rather than the anonymous folk in the snaps, the wind becomes the key protagonist and Pound’s muse. In Same place different people a series of characters seem to share no obvious relation other than sharing the same seat. Both works take ordinary moments, and through multiplying them and presenting them alongside each other, transform them into something altogether more mysterious and meaningful.

Portrait of the wind (detail) 2012 © Patrick Pound

Penelope Umbrico’s photo-based installations, video, and digital media works explore the ever-increasing production and consumption of images on the Internet. Navigating between consumer and producer, materiality and immateriality, and individual vs. collective expression, she views all images within this emergent environment as evidence for something other than what they depict. Her project Suns (from Sunsets) from Flickr adorns an entire wall in The Big Picture. Sunsets, Umbrico discovered, were the most popular subject matter on photo-sharing site Flickr. The excessive collage of virtual sunsets may not recall the experience of the sublime, but as we encounter its multitude of images we also encounter a multitude of people. Knowing that they share something in that moment, that none of us can express in words and all of us try to in pictures, is in itself quite an experience.

Where Umbrico’s suns bathe the gallery in the bright orange, red, blue and purple hues of fading days, on the mezzanine Daniel Connell’s video installation Lightless descends us into darkness - except for the flickering of artificial lights on the blink. As the glow of Lightless floods and fades it continually changes the illumination of the space, poetically asking us to reflect on our era of fickle technological dependence, in which the big questions might be the brevity of light and the inevitability of demise.

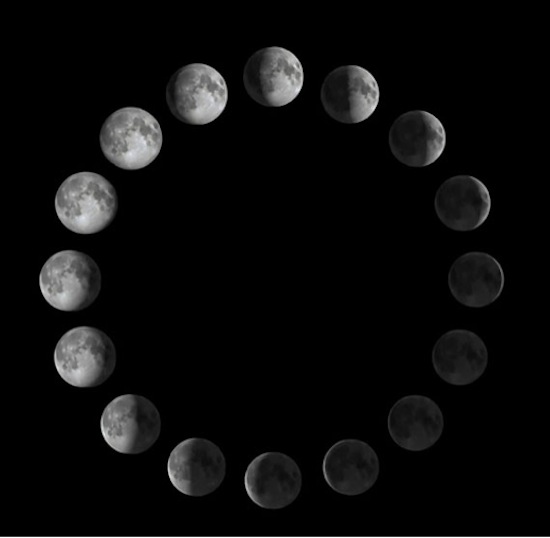

Loading Cycle 2011 © Drew Flaherty

Nighttime reappears in The Big Picture, with the lunar cycle. Except that here the moon’s reflected light is digitally animated to recall the illusory spinning motion of online loading icons. Drew Flaherty has manipulated the order of waxing and waning, and the speed of the moon’s journey between new and full, to create the soothing, almost meditative Loading Cycle. This visual pun plays on our relationship to both the networked and natural worlds, which in their different ways quite profoundly map our experience of time, and affect our moods and emotions.

Flow (detail) 2012 © Tim Webster

With waterfalls and mountain vistas, Tim Webster and Gemma Messih bring us back down to earth. Messih combines raw materials, found images and performative gestures in installations that tease the odd ways we use photos not to engage with nature but to remove ourselves from it. In Someone else’s horizon for example, a sunset hangs in tatters following the artist’s failed attempt to inhabit the romantic scenario, instead coming out the other side. Although their approaches are worlds apart, Webster like Messih splinters our safely seductive recordings of nature. Shot on location at a site of iconic natural beauty, the South American Iguazu waterfalls, Flow is immediately spectacular and captivating. Webster however disrupts the cliché of beauty, using temporal and spatial fracturing to break our simplistic perceptions of nature whilst revealing a reliance on technology to freeze memory, substitute experience and replace the real with the re-lived.

Each one of these artists explores photomedia’s capacity to bring us both closer to and further from the world we inhabit. Often it seems, like a camera’s zoom, we have to choose between a focus on the details or a larger frame of reference. In sidestepping traditional lens based practices their works avoid this duality, and instead suggest that, while the big stuff counts, noticing the small things is equally important.