© Elin O'Hara Slavick

The Daylight Project Space 121 W Margaret Ln Hillsborough, NC 28697 États-Unis

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. bomber Enola Gay released an atomic bomb over the city of Hiroshima, killing 70,000 people instantly (with another 70,000 dying by year’s end from their injuries). While many are aware of this catastrophic event that ushered in the Atomic Age, the aftermath of the bombing is less well documented, and the United States in particular has paid little attention to preserving a visual record.

American artist elin o’Hara slavick (born 1965) was raised in Portland, Maine by activist parents who were engaged in the anti-war and anti-nuclear power movements.

Her first memory of Hiroshima is attending a Hiroshima Day memorial service in Portland’s main square on August 6 in the 1970s during which she read a firsthand account of the atomic bombing by a woman who survived it as a little girl. She was unable to get through the story without choking up. Slavick’s art, which explores ethical ways of visualizing the barbarism of war, is informed by the activist environment of her early childhood.

© Elin O'Hara Slavick

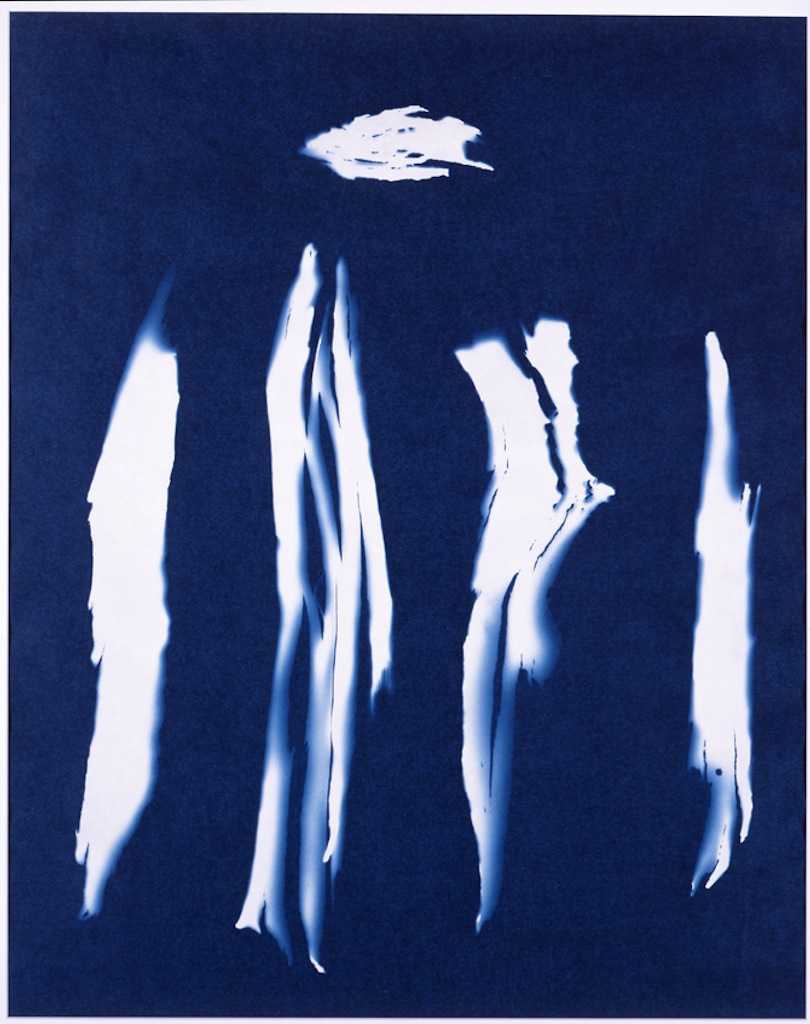

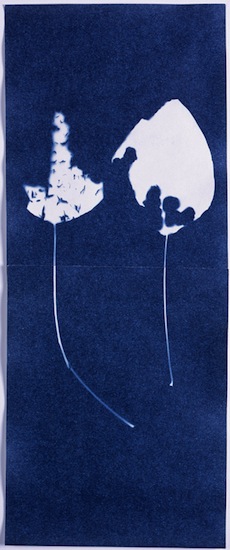

After Hiroshima (Daylight Books, April 2013) is slavick’s attempt to visually, poetically, and historically address the magnitude of what disappeared and what remains as a result of the dropping of the A-bomb. These are images of loss and survival, fragments and lives, architecture and skin, surfaces and invisible things — like radiation. Slavick’s quiet and sensitive photographs are in sharp contrast to the painful, graphic images associated with the aftermath of Hiroshima. In his essay, James Elkins describes After Hiroshima as a « sharp, sad and beautiful project. » The book combines cyanotypes that evoke the early days of photography, rubbings, and traditional photography made by slavick over the course of visits to Hiroshima with her family from 2008 through 2011. The accompanying texts are published in English and Japanese.

The process of exposure is critical to slavick’s work — exposure to radiation, to the sun, to light, and to history. The subject of slavick’s cyanotypes are A-bombed objects borrowed from the collection of the Hiroshima Memorial Peace Museum, many donated by victims of family members, among them a slender comb, a round canteen, a deformed glass bottle, a piece of melted metal, and a belt buckle. She also gathered natural forms from local parks, bits of dead flowers (presented on the book cover), leaves, and tree bark. She placed the specimens on paper soaked in cyanide salts and exposed them in natural sunlight. These relics that were exposed to massive doses of radiation over 67 years ago, are exposed again here by slavick as ghostly white shadows floating in a sea of indigo blue. From the artist’s perspective, they memorialize those that vanished in the first seconds of the blast leaving behind their own white shadows. The work brings to mind the ethereal 19th century botanical photographs of Anna Atkins.

Another series presents photographic prints of rubbings of A-bombed surfaces and objects located around the city, including a bridge, a bank countertop, a floor, a keyhole, a tree, and a rusty door. Slavick placed Japanese paper directly onto the surface and rubbed it with a black wax crayon to create a « negative » which was then made into a silver gelatin contact print. Through this tactile, intense process, she traced, touched, and « photographically » documented the many sites of survival, destruction, and exposure. The book also includes traditional photographs of atomic traces that are visible everywhere, including an image of an A-bombed weeping willow tree that her children touched and kissed while saying « sorry. »

Through her shadowy, poetic images, slavick captures the very essence of a profound event that many are still grappling to understand. As the first American photographer to gain access to document the artifacts of the Peace Museum, she faced the challenge and responsibility of capturing the enormity of Hiroshima in a manner that was ethical and reverential. Her resulting work is complex, and confronts with dignity and tenderness the irreconcilable paradox of making the barbaric visible, as artist, viewer, and witness.

There is a book with Daylight book and the link of the website:

http://daylightbooks.org/"

Photos and vignette © Elin O'Hara Slavick