![Weegee, [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York], January 16, 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography

Medium: Gelatin silver print](/files/news_20822_0.jpg)

Weegee, [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York], January 16, 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography Medium: Gelatin silver print

ICP (International Center of Photography) 1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street New York États-Unis

Gangland murders, gruesome car crashes, and perilous tenement fires were for the photographer Weegee (1899—1968) the staples of his flashlit black-and-white work as a freelance photojournalist in the mid-1930s. Such graphically dramatic and sometimes sensationalistic photographs of New York crimes and news events set the standard for what has since become known as tabloid journalism. In fact, for one intense decade, between 1935 and 1946, Weegee was perhaps the most relentlessly inventive figure in American photography. A surprising new exhibition at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street), titled Weegee: Murder Is My Business and organized by ICP Chief Curator Brian Wallis, will present some rare examples of Weegee’s most famous and iconic images, and will consider his early work in the context of its original presentation in historical newspapers and exhibitions, as well as Weegee’s own books and films.

Taking its title from Weegee’s self-curated exhibition at the Photo League in 1941, Murder Is My Business looks at the urban violence and mayhem that was the focus of his early work. As a freelance photographer at a time when New York City had at least eight daily newspapers and when wire services were just beginning to handle photos, Weegee was challenged to capture unique images of newsworthy events and distribute them quickly. He worked almost exclusively at night, setting out from his small apartment across from police headquarters when news of a new crime came chattering across his police-band radio receiver. Often arriving before the police themselves, Weegee carefully cased each scene to discover the best angle. Murders, he claimed, were the easiest to photograph because the subjects never moved or got temperamental.

Weegee’s rising career as a news photographer in the 1930s coincided with the heyday of Murder Inc., the Jewish gang from Brownsville who served as paid hitmen for The Syndicate, a confederation of mostly Italian crime bosses in New York. As a wave of governmental and legal crackdowns swept the city between 1935 and 1941, the rate of organized murders of small-time wiseguys and potential stool pigeons increased dramatically. Weegee often worked closely with the police but also befriended high-profile criminals like Bugsy Siegel, Lucky Luciano, and Legs Diamond. Weegee called himself the “official photographer for Murder Inc.” and claimed to have covered 5,000 murders, a count that is perhaps only slightly exaggerated. In asserting the true nature of his business, Weegee proudly displayed his check stub from LIFE magazine that paid him $35 for two murders, slightly more, he said, for the one that used more bullets.

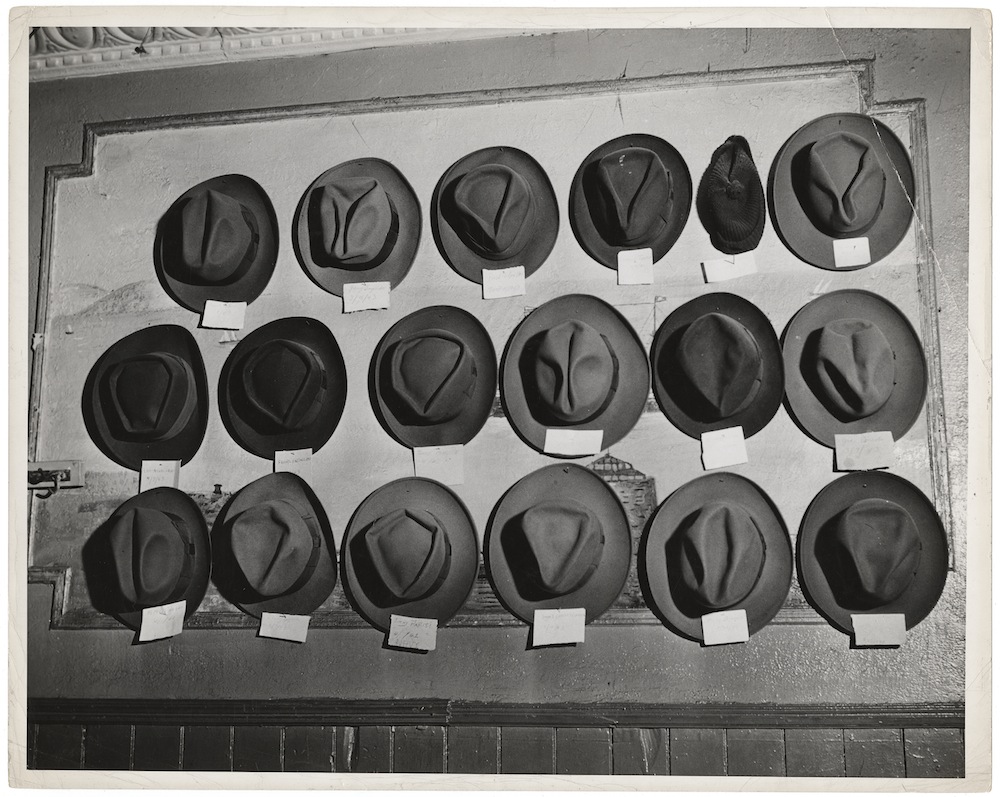

Weegee, [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York], ca. 1943. © Weegee/International Center of Photography.

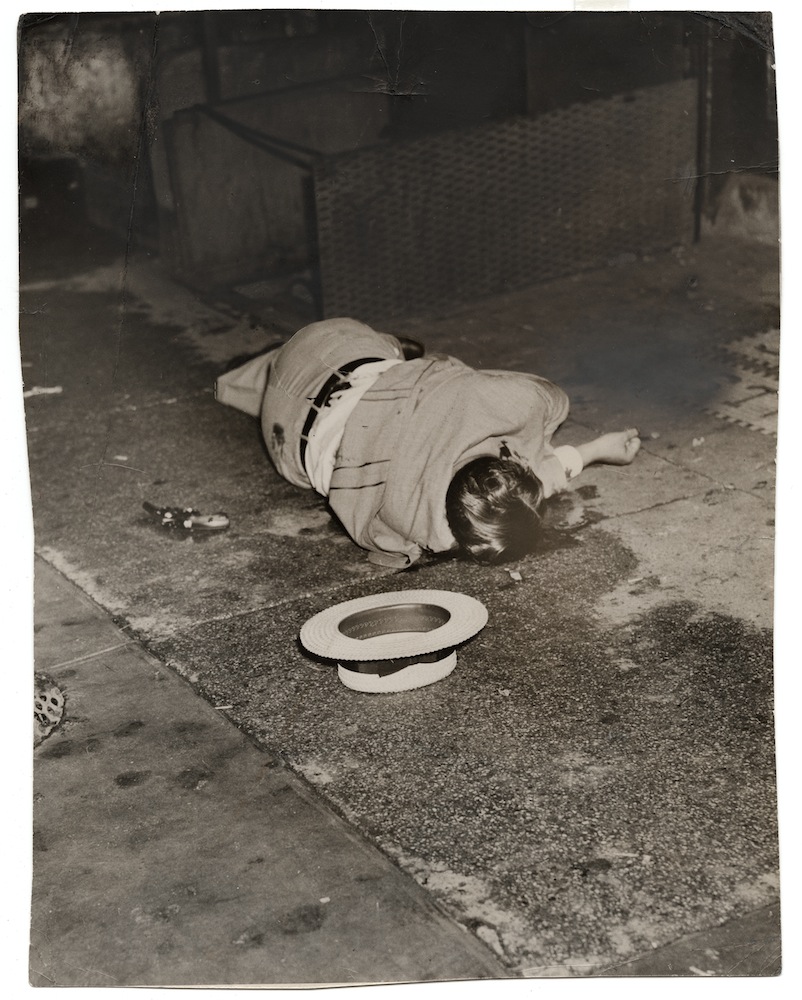

Weegee, [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York], August 7, 1936. © Weegee/International Center of Photography.

Selling his photographs to a variety of New York newspapers in the 1930s, and later working as a stringer for the short-lived daily newspaper PM (1940—48), Weegee established a highly subjective approach to both photographs and texts that was distinctly different from that promoted in most dailies and picture magazines. Utilizing other distribution venues, Weegee also wrote extensively (including his autobiographical Naked City, published in 1945) and organized his own exhibitions at the Photo League, the influential photographic organization that promoted politically committed pictures, particularly of the working classes. In 1941, Weegee installed two back-to-back exhibitions in the League’s headquarters. This visibility helped promote Weegee’s growing reputation as a news photographer, and he began stamping his prints “Weegee the Famous.” The general acceptance of his punchy photographic style, which did not shy away from lower-class subjects and humanistic narratives, led to the acquisition of his work by the Museum of Modern Art and inclusion in two group shows there, in 1943 and 1945.

“Weegee has often been dismissed as an aberration or as a naive photographer, but he was in fact one of the most original and enterprising photojournalists of the 1930s and ‘40s. His best photographs combine wit, daring, and surprisingly original points of view, particularly when considered in light of contemporaneous press photos and documentary photography. He favored unabashedly low-culture or tabloid subjects and approaches, but his Depression-era New York photographs need to be considered seriously alongside other key documentarians of the thirties, such as Dorothea Lange, Robert Capa, Walker Evans, and Berenice Abbott,” said Wallis.

The exhibition will feature over 100 original photographs, drawn primarily from the comprehensive Weegee Archive of over 20,000 prints at ICP, as well as period newspapers, magazines, and films. It will also include partial reconstructions of Weegee’s studio and his Photo League exhibition. The four galleries will each feature a touch-screen monitor allowing visitors to explore further details regarding the images and artifacts in that room.

This exhibition was made possible with support from the ICP Exhibitions Committee, The David Berg Foundation, an Anonymous donor, and with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. The touch screen content was produced by Documentary Arts in association with Octothorp Studio.

Vignette : Weegee, [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York], January 16, 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography