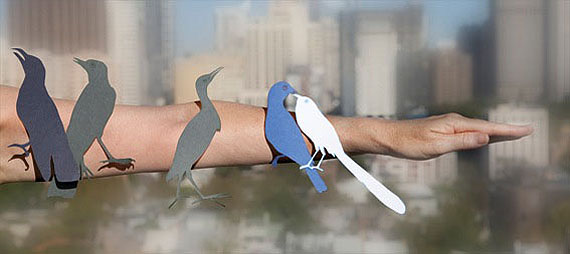

Anne Ferran, Birds of Darlinghurst (dollarbird, Australasian pipit, little bittern, indeterminable, emu wren, series: Birds of Darlinghurst, 2011

Stills Gallery 36 Gosbell Street, Paddington NSW 2021 Sydney Australie

“Ferran’s practice…focusing on incidental details and overlooked subjects, combining the indexical authority of the photograph with the sensorial resonance of symbolic objects and materials, brings history up against itself, up against its desire to differentiate itself from the now. Ferran’s work instead insists on confronting us with the past’s tenacious persistence." Geoffrey Batchen,The ground, the air catalogue 2008

Like many people, Anne Ferran keeps a close eye on the birds around her - would give a lot to understand their social life, but mostly it remains a mystery. She made a discovery last year that intensified this interest: the on-line existence of the paintings of the artists of the First Fleet, in the collection of the Natural History Museum in London. The First Fleet artists painted the birds they encountered on arrival and that shared their strange new world more often than any other subject.

The paintings are detailed and descriptive, full of character and individuality. Ferran found herself imagining the encounters that might occur between races or species of birds that were new to one another. This led to a video work, Songbirds are Everywhere, where brief encounters play out between small bird shapes based on the original paintings.

Most of the artists gave their painted subjects an English common name; some have persisted while others have fallen into disuse. Ferran’s regret for the loss of bird names like agile creeper, bold vulture, doubtful thrush, velvet-faced crow is real, but mild compared to the loss of the indigenous Eora names that at least one artist made a point of recording. Her photographs of small nets flung into the air preserve a few of these obsolete English names as titles.

___

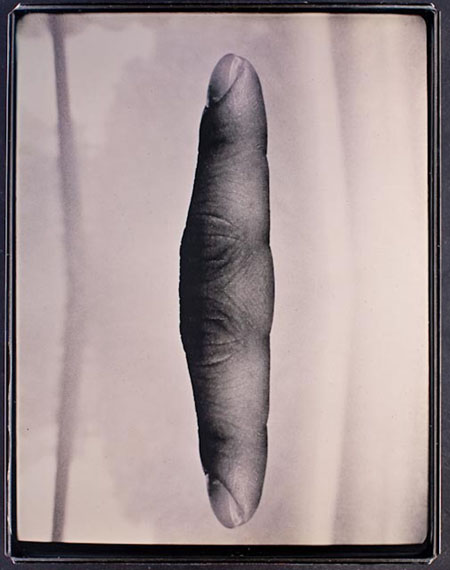

For the last decade, Aaron Seeto has been interested in archives, in particular family photo albums and other photographic records. This interest is mostly based upon a desire to make visible the alternate historical positions and experiences of families such as his own Chinese-Australian one. He is interested in the malleability of the narratives, which surround archive records - how images degrade, how stories are formed and privileged, how knowledge and history is written. In recent bodies of work exhibited here Fortress and Oblivion, Seeto has utlilised the daguerreotype, one of the earliest and most primitive photographic techniques. Not only is the chemical process itself highly toxic and temperamental but the daguerreotype’s mirrored surface means the image appears as both positive and negative, depending on the angle of view. For Seeto, this mutability captures the essence of our experience of history and memory.

In Fortress Seeto presents a series of daguerreotype photographs that use images of the artists' own body connecting in physically impossible ways. Body parts are mirrored and repeated in absurd combinations. These errant double fingers and replicating heads seem like specimens from a science experiment gone wrong and recall the early understanding of photography as document and fact. At the same time there is a hint of theatricality and magic about these works, perhaps also suggesting that ‘self’ is as slippery as a concept as ‘truth’. The 3 channel video work Fortress, included in the exhibition, was produced in collaboration with Seeto’s family. The video isn't a portrait of his family, as much as it's a portrait of a space. Fruit trees, patio, grass, a red brick house – this generic image of suburbia is given a nostalgic and mysterious treatment. Fortress is based on questioning how to articulate or write a history of day-to-day experiences, especially those experiences that exist outside of the cultural and social mainstream. Who controls and what is controlled? Who protects and what or who is protected?

Aaron Seeto

Fortress (Returning Finger #1), 2011

from Fortress

Daguerreotype

Also exhibited will be works from Seeto’s ongoing series Oblivion in which he sourced details from images of the Cronulla riots of 2005 found on the internet. In reproducing these as daguerrotypes he seeks less to represent the incident than to look at how it was reported, understood and remembered. The instability of the virtual information found online is echoed in the photographic process.