Expositions du 12/10/2005 au 10/12/2005 Terminé

Young Gallery 75b Avenue Louise 1050 Bruxelles Belgique

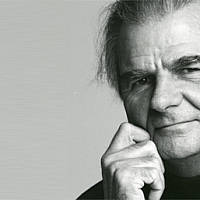

It is not exactly a scene from Blow-up, the 1996 movie that established the fashion

photographer as the totally hip icon of the swinging ‘60s. But the three-floor studio in

Manhattan's Chelsea district belonging to Patrick Demarchelier, one of the hottest

names in the business, does indeed buzz. Phones ring constantly, music blares from

unseen speakers, and fresh-faced young things of both sexes bustle around the big, airy spaces. On one floor is a styling area with bright lights and glowing mirrors, on another is Demarchelier's own printing studio, and on yet another, a table top mock-up of the photographer's retrospective that was recently on view at Milan's Museum PAC (Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea) and may travel to venues in Moscow and Brazil. Demarchelier himself projects an aura of calm, an almost seigneurial aplomb as he conducts a tour of the premises. A tall, rugged-featured, shaggy-haired Frenchman, he speaks a rapid-fire, heavily accented English, stopping here to oversee the work of a retoucher who could pass for a model, there to consult with an assistant on the specifics of his museum display. The 61-year old photographer seems unfazed that he has shot some of the most beautiful women in the world and many of the most famous faces of our time. It's easy to understand why the late Princess Diana or Warren Beatty would hand over to him disarmingly candid moments. As Martin Harrison, one of the organizers of the Milan show, writes, Demarchelier's “charm and naturally relaxed personality break down

his sitters' inhibitions and encourage them to place their trust in him.”

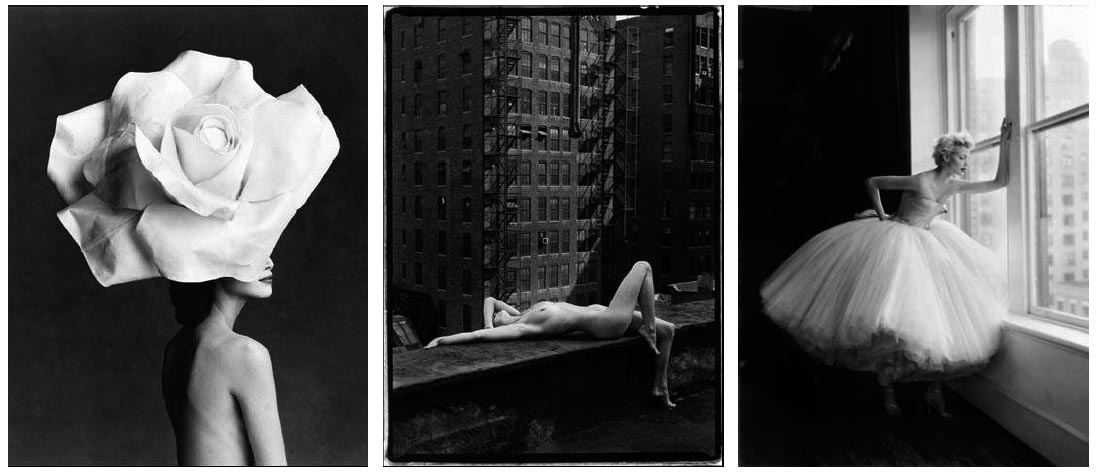

Demarchelier also offers up images of a world far removed from the hothouse of high fashion. His second one-person show at New York's Tony Shafrazi Gallery last year included shots of Tibetan monks, Sumo wrestlers, and African landscapes, along with the glitzier farenude models frolicking underwater, celebrities, and, of course, Christy, Cindy, and Naomi. For

Demarchelier, it doesn't take much to make a fine photo. “Good photography comes from

photographing every day,” he says. And “art is everywhere. Some days you create pictures

that can be art. Some days you don't .” Though largely panned by critics (the work “oozes false sincerity.” said one), the show did “ extremely well,” according to Shafrazi. Aside from coaxing obvious goodwill from his subjects, Demarchelier's photographs are remarkable for the effects he produces with light, air, and water. He was born near Paris in 1943 but grew up in the northern French port and industrial town of Le Havre. Significantly, the proto-Impressionist painter Eugene Boudin came of age not far from the same town, along an estuary of the Seine at

Honfleur, and critics have seen similarities between the two in their penchant for brilliant light. Demarchelier confesses to having looked at Boudin when he was younger and praises

“the amazing lighting in his pictures.”

The photographer received his first camera for his 17th birthday, and soon after he got a job printing and retouching passport pictures. He moved to Paris at the age of 20 and landed in another laboratory, printing news photos. Before long, he was the house photographer for the Paris Planning model agency and then an assistant to Hans Feurer, an art director turned photographer who worked for the British magazine Nova and Vogue . Demarchelier proved an apt pupil and was soon producing his own spreads and covers for Marie-Claire and Elle , among other magazines. Inspired by Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, he was one of a group of young shooters who reacted against the high seriousness of fashion photography of the time in favor of informal and spontaneous images.

The qualities he looked for then, as today-- ”expression, emotion, something alive”--

brought him to attention of the late Alexander Liberman, creative director of Vogue . By 1974 Demarchelier was working for the American edition of the magazine, and the following year he moved to Manhattan. For the last decade, Demarchelier has been poised at the top of an extremely competitive field, a position he chalks up to his ability to work as part of a team. Others point to his incredible speed and unerring eye.

“He is the most technically brilliant fashion photographer, and he has a great deal of style,” says Katherine Betts, the editor of Harper's Bazaar . Though he admits to a handful of predictable influences--Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Edward Weston--Demarchelier also spends a fair amount of time in museums, looking especially at Impressionist and modern art. “I love Gauguin, but right now I'm more

interested in contemporary art,” he says. His own collection is heavy on recent expressionist painters, such as Francesco Clemente, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kenny Scharf. The common thread in his work and theirs may be an affection for wild things both real and imagined, which comes through in his photos of animals and exotic landscapes, included in Patrick Demarchelier : Exposing Elegance, a monograph published in 1997 by Shafrazi to accompany a show at his gallery.

Affection shines through, too, in Demarchelier's photos of his family. On the wall of one studio hangs a shot of his son Arthur on crutches, with a leg in a cast from a skiing accident. The boy is grinning broadly in spite of the mishap. Other photos, published recently in Harper's Bazaar, show Demarchelier at ease in the Caribbean with his striking wife and sons. Clearly, the camera is kind to the clan in more ways than one. (Aside from a vacation home in the West Indies, he owns an apartment on Central Park West and a weekend house in the Hamptons.) In his work, Demarchelier says, he is “ always looking for change,” but in his life, it seems, stability and harmony provide the defining balance.

Ann Landi

Young Gallery 75b Avenue Louise 1050 Bruxelles Belgique