Huis Marseille Keizersgracht 401,The Netherlands 1016 EK Amsterdam Pays-Bas

This fall Huis Marseille will be holding a retrospective exhibition of work by the Indian photographer Dayanita Singh (New Delhi, 1961). In 2008 she received an award from the Prince Claus Fund for her discerning view of life in India and for bringing new aesthetics to Indian photography. Singh is internationally recognized for the highly expressive and poetic quality of her photographs, whose incidence of light and visual construction are so meticulously composed that they result in a comment on society and her own past.

Dayanita Singh was trained as a photojournalist at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP), which she attended after her study of graphic design at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad. On her return to India in the late 1980s, Singh began photographing evidence of social injustice for newspapers and magazines, hoping, as so many photographers had hoped at that time, to make a difference. In her work she challenged the prevailing notions of photojournalism which then still revolved, from an aesthetic point of view, around ‘the decisive moment’: the point at which the photograph’s content and form correspond perfectly.

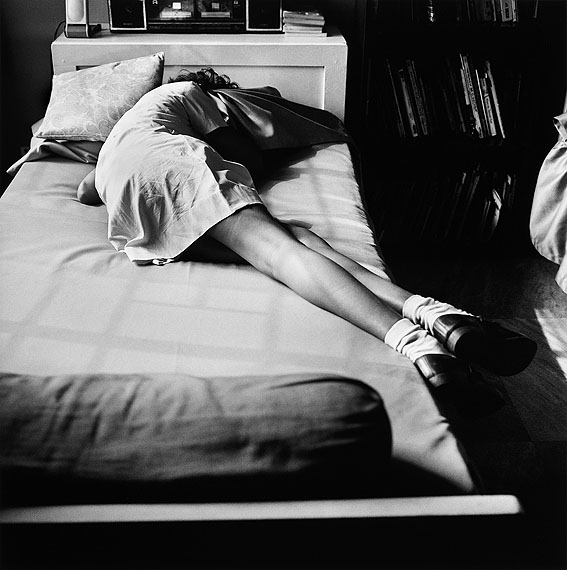

By the early 1990s Singh was aiming her camera more and more at her own surroundings, no longer feeling at ease with her journalistic work. Her series on the eunuch Mona Ahmed (1989–2001) developed on the basis of a journalistic assignment, but it represents a critical point at which Singh chose to go her own way and depart from prevailing Indian views on photography. Mona, who became a close friend, has prompted a body of work in which the photographer’s personal relationship with the subject has key significance, both directly and indirectly. The same can be said about I am as I am (1999), an intimate series portraying girls in an ashram, a religious community in Benares to which Singh gained access through family ties.

In terms of the photographic form as well, Singh shifted course by switching, in fact, from her 35mm and medium format 6 x 7 camera’s to a Hasselblad camera. This camera’s square format forced her to observe and photograph in a different way: more slowly and precisely, with greater concern for composition, cropping, detail and light. That period brought about the formal and monumental portrait series Ladies of Calcutta (1997–1999) and Bombay (2002), in which she shows the world of her own origins – that of her family and friends from the higher social classes. What we see is a lesser-known facet of India, one of postcolonial prosperity and of well-to-do women in their comfortable homes, surrounded by traditional Indian symbols. With Go Away Closer (2007) Dayanita Singh begins working in an increasingly free and associative manner. The absence of people is manifest in empty rooms and spaces and in remarkable still lifes of everyday objects. People are also emphatically absent from her most recent series, Blue Book (2009) and Dream Villa (2010), yet they do remain omnipresent in details and even in the color and light. The urban scene full of movement and vigor has turned into a desolate, surreal world that offers an endless range of interpretations and meanings.

Sent a Letter, the book project that Dayanita Singh carried out with Steidl in 2007, is a minimuseum that the visitor can take home in the form of a box containing seven booklets. Each is bound in leporello form and contains photographs of a specific trip – to Calcutta, Mumbai, Benares, Allahabad, Devigarth and Padmanabhapuram?that had special importance to her. One booklet shows photographs of her mother Nony Singh, who was also a photographer. The small size of the object heightens the sense of intimacy in the images, but because no texts or captions appear in it, Dayanita Singh allows her own experience to be open to everyone’s own associations.

This exhibition has been organized by the Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid, and installed here by Huis Marseille in collaboration with guest curator Carlos Gollonet and the photographer.