The Wapping Project Bankside 37 Dover Street, Ely House W1S 4NJ London Royaume-Uni

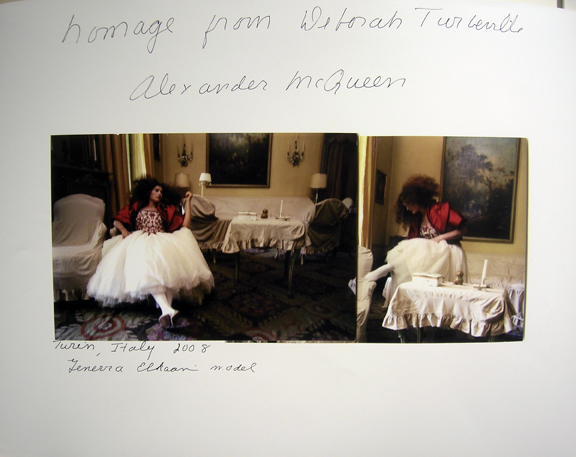

One of the world’s most important female fashion photographers headlines her UK show with a tribute to Alexander McQueen.

The Wapping Project Bankside, a new gallery space adjacent to Tate Modern, will host a solo exhibition by Deborah Turbeville one of the most important fashion photographers of the 20th century.

A selection of 30 images will be on show at The Wapping Project Bankside, spanning Turbeville’s extraordinary career so far. Among the images is ‘Homage to Alexander McQueen', a personal expression of Turbeville’s bereavement at losing a friend and collaborator.

Like her near contemporaries, Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, Turbeville rethought and recast fashion photography in the 1970s. But perhaps even more than her male counterparts, Turbeville injected narrative and mystery into assignments for, amongst others, American Vogue and Harpers Bazaar.

Turbeville’s pictures are as much riddles as they are images. Consciously damaged goods, they are blurry, grainy, tormented into painterly colours, scratched, marked or sellotaped. 'I destroy the image after I've made it,' said Turbeville. 'Obliterate it a little so you never have it completely there.' It's a quite un-American world, a view through the rear window, fascinated by the beaten, worn and forgotten.

Turbeville took her first pictures in 1966. They were blurry but when she showed them to Richard Avedon he liked them, blurs and all. Avedon taught Turbeville technique and by 1972, she was working as a photographer. An early shoot for Vogue was of girls in bikinis at a cement works. These were hailed by Conde Nast's editorial director Alexander Liberman as 'the most revolutionary pictures of the time.’

But the work that made Turbeville’s name is the 'bathhouse' series she took for American Vogue in 1975. In this fashion story she shot a series of images of barely dressed women, wet and languid and almost kitsch. Even now the pictures hold the sense that the women are prisoners, of what is not clear, and while undeniably beautiful the images have an unsettling undercurrent – it has been said they look like they're in gas chambers.

If one of photography's most honourable impulses is to subvert - or to flee from - the medium's inherent voyeurism, Turbeville collapses this paradox by succumbing to it. Turbeville's naked, wet women are under no illusion that the photographer is there. They acknowledge her presence. They maybe even watch us, the viewer.

'I go into a women's private world, where you never go,' Turbeville said. 'It's a moment frozen in time. I like to hear a clock ticking in my pictures.'

Commenting on the Deborah Turbeville show, Wright says:

“I have long championed the work of Turbeville and mounted a major exhibition of her work at the Wapping Project in 2006. What continues to captivate me about Deborah’s work is a feeling that you are somewhere in the past; a languid, barely sexual past of white, willowy women, distressed prints and a sense of a narrative interrupted. Even now her pictures have a luminous quality which is without equal.”