Iranian contemporary art, with the exception of the cinema, has only swum into western consciousness fairly recently. Because of the political tensions between the West and Iran, it is still largely misrepresented and misunderstood. Before looking at the specific cases offered by this exhibition, there are some general observations to be made. The first is that Iran possesses an extremely ancient culture, going back some three thousand years. The art of the present day has deep roots in that culture – to an extent often missed by western observers. The second is that Tehran, the largest city in the Middle East, with a population of nearly 8 million, has a lively indigenous art world. Most of the leading Iranian artists still live in their own country, at least part of the time and are proud to do so. The third is that, despite the Iranian Islamic Republic’s reputation for moral repression, the Iranian art of the present is often paradoxically very much concerned with the human body, and is frequently subtly infused with sexual connotation. The present show is designed to illustrate that fact.

Its contents will come as no surprise to anyone who has either visited Tehran, or who has any acquaintance with earlier Persian art and literature. Safavid miniatures from the time of Shah Abbas (1588-1629) often illustrate erotic subject matter. Hafez, Iran’s best-loved poet (ca. 1320-1390), as the entry on him in Wikipedia notes, “took as his major themes love, the celebration of wine and intoxication, and exposing the hypocrisy of those who have set themselves up as guardians, judges and examples of moral rectitude.” Striking features of today’s Tehran cityscape are huge propaganda murals. Many celebrate the tragic heroes of the bloody Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88. They are linked to an age-old Shia cult of martyrdom, but the protagonists are represented as if they were Hollywood film stars, looking out from the billboards on the Los Angeles Sunset Strip. With their handsome features and swimming eyes, these handsome young men seem designed to have an erotic appeal to men and women alike.

The exhibition offers the work of five artists, two men and three women. The work of the men, Fereydoun Ave and Ramin Haerizadeh, demonstrates clearly how firmly rooted Iranian contemporary art is in Iranian popular culture. Fereydoun Ave’s series of digital prints, Rostam in Late Summer Revisited, refers to one of the heroes of the great Iranian epic, the Shahnameh or Book of Kings, written by the poet Ferdowsi around 1000 a.d. As Iranians know, Rostam's symbolic attributes of manly strength and martial valor reappear today in the wrestlers known as pahlavans, who are practitioners of a traditional Sufi cult of physical exercise. This cult of wrestling permits a greater degree of male nudity than is usually permitted in Iran, and encourages an admiration of the male body.

Ramin Haerizadeh’s Men of Allah series, with its lubricious, effeminate mullahs, based on self-portraits of the artist, is inspired by a kind of Iranian folk theater called Taaziye, popular in the 19th century and still current today, where women’s roles are played by men. In one scene, much liked by the Iranian public, the brother of Imam Hossein, the founder of the Shia branch of Islam, is married to a chador-clad female who turns out to be a bearded man. The result, in Harizadeh’s hands, is a sly satire on clerical manners and morals. It is worth noting that Iran is the only Islamic nation with a strong theatrical tradition, which often relates, as here, to an equally strong tradition of figurative art. This tradition embraces images of effeminacy as well as images of strength, as is witnessed by the numerous portrait miniatures of seductive page-boys from the time of Shah Abbas.

The images offered by the three women artists are even bolder than those offered by the men. Aficionados of contemporary art who know little or nothing about Iran are always surprised to discover how many gifted women artists the country produces. Yet the Iranian artist with the biggest international reputation is undoubtedly Shirin Neshat, who remains true to her roots though she has now lived for many years in America. Another reaction, when westerners discover that women create a good deal of the most interesting art now being produced in Iran, is to assume, despite this, that women artists are constantly inhibited by a struggle against the conditions Iranian society imposes on them.

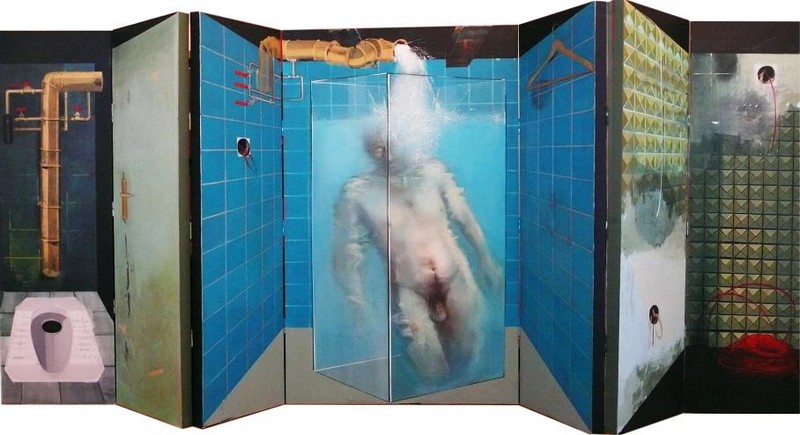

The truth is that Iranian art made by women does have a strongly feminist streak, but that this feminism is different from its western equivalent. In particular, women artists living and working in Iran do not want to give up their roots in Iranian culture, and are offended to be thought of as being victims perpetually preoccupied by victimhood. The three artists featured here have been chosen to illustrate the boldness of their approach. Nikoo Tarkhani deals with the female body, and her sometimes fragmented nude self-portraits powerfully convey her sense that women in a contemporary Islamic society are struggling to piece together a contemporary identity. They can be compared, in this sense, with the very different self-portrait images of Ramin Haerizadeh. Mitra Farahani, who is a film maker in addition to being a painter and a maker of graphic works, tends to focus on the naked male body, which she treats on occasion with a boldness that easily exceeds most of the treatments of this subject one sees in the West. The sculptor Narmine Sadeg seems to refer to the strong tradition of puppet theater in Iran. The Iranian director Behrouz Qaribpour has become internationally famous for his puppet opera presentations, and recently received a major Italian award for his work. The puppet plays are closely related to the Taaziye school of live theater. The word Taaziye means ‘elegy’, and productions are typically presented in connection with the Day of Ashura, when Shia Muslims lament to death of the Imam Hossein. They can be thought of as the equivalents of Christian Passion Plays, yet, like the Passion Plays of the Middle Ages, tragic subject matter does not exclude an element of robust humor. It is noticeable not only that Sadeg’s figures can be swung about at will on the rods that pierce and support them, but also that her nude males have conspicuously small genitals. As a result they seem like images of powerlessness - a retort to Fereydoun Ave's images of strength.

Iranian contemporary art is constantly in dialogue with the society that surrounds and supports it. Like art in many Middle Eastern and Far Eastern societies, it invites the spectator to read visual images on several different planes, both linear and temporal. This gives a resonance and depth that is now often lacking in western equivalents.

Edward Lucie-Smith