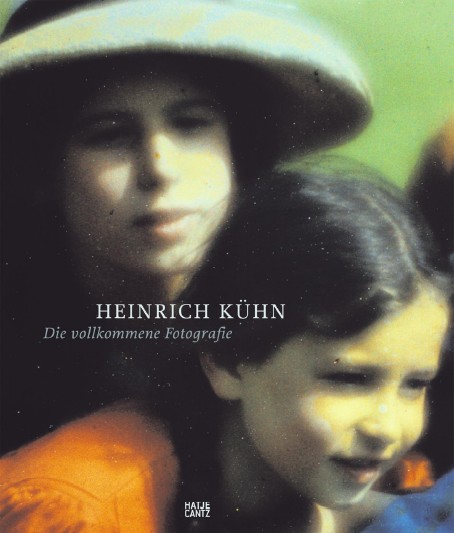

Heinrich Kühn’s lifelong goal— and one of the original ideas in international photography around 1900— was to use the photographic image as a way to realize an artistic vision as precisely as in painting or drawing. Along with Alfred Stieglitz and other friends, Kühn made the stylized photograph an element of the total work of art, which the Secessionists strove for. The most important tool for this was a pigment process perfected by Kühn, in which the free choice of paper and pigment made the picture look more like a print than a conventional photograph. This allowed Kühn to alter the brightness contrast to fit his idea of the image, minimizing the sharpness of the image (rejected as “non-artistic”) as much as he pleased. Around 1910 Kühn reduced the romantic world of “pictorialism” to the point where his compositions became almost abstract, with a sense of timelessness and balance.