Nobuyoshi Araki’s recent Koushoku Painting show at Rathole Gallery (October 17 – December 7, 2008) featured 10 very large silver gelatin black and white prints that Araki had then painted over with various colors. Most of the photos depicted different models in various states of bondage, or “kinbaku” as it is known in Japanese. This is of course very familiar territory for Araki, and on first thought it was hard to get excited about the prospect of seeing more of these, but the show was well worth seeing.

The majority of the painting has been applied in an abstract way, splotches of color here and there, brushstrokes here and there, all with bright, primary colors. While the paint obscures what we can see in the photos — sometimes frustratingly so — it is also quite appealing in its own right. There were also more literal uses of the color, such as in one photo where an eating fork looks to pierce the model’s breast, and here starts a brilliant red daub of paint that eventually runs down the remainder of the canvas. It’s obvious to be sure, but coupled with the artifice of the photo itself, it seemed in keeping for this “wound” to erupt in blood-red paint splotches.

On a purely visual level, the works were stunning. The size of each canvas (each over 130cm by 160cm), the sumptuousness of the black and white, and the vibrancy and texture of the color paint, created works which were gorgeous to look at, despite whatever reservations one might have about the subject matter.

“Coming from crude triangular cut-outs hiding the genitalia, to be confronted with life-size, full-blown labia, was needless to say a rather breathtaking experience.”

Personally I found the works to be highly erotic, which was surprising to me. Frankly I have never cared for this side of Araki — nor of this side of Japanese sexuality and eroticism. Although I realize that I’m looking at it via Western eyes, it remains for me threatening, violent, and when you get right down to it, just not my cup of tea. Despite these prejudices, however, I found myself quickly warming to the idea that there might be more to this art form — and Araki’s treatment of it — than I previously was prepared to cede.

One thing that immediately jumps to mind when you look at the works is that it isn’t often you see such unabashed exposure of the female nude form, especially in Japan with its somewhat outdated restrictions against showing the pubic area. Araki’s own early books are a perfect example of this censorship, with their crude triangular cut-outs hiding the genitalia. Coming from this, to be confronted with life-size, full-blown labia, if you pardon the expression, was needless to say a rather breathtaking experience. More than erotic though, the pictures were very beautiful. And, as with a lot of Araki, they are also ugly and base.

One of the most arresting pieces in the show was one where the model has been suspended in mid-air by ropes. Because we don’t get to see the apparatus by which she is hanging — coupled with her calm, reposed expression — the ropes lose something of their menace. The model seems to be floating, like a diver in water, or an astronaut in gravity-less space. Unlike other kinbaku of this type, where an apparatus is used to suspend the woman in mid-air, and where the photos of models suspended like this are often shown hung upside down, or with their bodies contorted, Araki instead opts for a frontal approach. The model faces us, her legs suspended with ropes in a way that makes her look like she is sitting down for us. It could almost be a portrait. As such, she is presented as a more complete entity than the models in other photos.

The background in this photo helps to set it apart. It is clear that it was shot in a traditional Japanese house, and through open doors we can see outside beyond the model to what we imagine is a Japanese garden. Whereas the other works’ settings have a decidedly Western — or neutral, in the case of one photo with a studio backdrop — feel, spaces enclosed by walls with peeling patterned wallpaper and occupied by old Europe furniture, the airiness of this particular setting enhances the floating impression. On the floor lies an object which looks like one of Feininger’s seashells or some kind of elongated snail. Compared to a Godzilla figure or a rubber lizard that feature in other works, it is non-threatening, but earthy, helping to collapse interior and exterior space. The model’s kimono pushes the traditional aspect further, as does her fringe haircut. With its elaborate design, its excess of material and folds, the kimono makes this particular model the most-clothed of those on display. It is therefore with some irony that anatomically speaking, this is the most exposed of all the models, and Araki has resisted obscuring the woman’s sex with daubs of paint as he has done elsewhere.

There is another work by Araki done along the same lines, not shown at the Rathole exhibition but included in the accompanying catalog. It makes for an interesting contrast with the just-described photo. Here too a woman is hoisted in the air. Again, we cannot see from where she is hanging, only that she is suspended in air, giving us the same sensation that she is not hanging so much as floating. And here too, the model assumes a calm, almost bored expression. However, unlike the image in the show, the background is yet another interior, with a mock-Doric column nightstand with a black cat doll atop it. More importantly, here the model is completely nude. Because she is without clothes, there is no mistaking that her hands are bound behind her back. In fact, the hands can be seen dangling behind her, like a perverted extension of her vagina, or something — a fish, a butterfly — emanating from it. It’s a disconcerting appendage, if you will, but it also viscerally notches up the woman’s vulnerability. It’s a shame there wasn’t enough space to include this and a couple of other works that are shown in the catalog.

“The lizard is a stand-in for a Warhol-like Araki that we know instinctively is just off-frame, turned on by the spectacle, and turned on by his control of the power cords.”

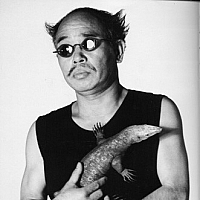

If it was possible to have a show-stopper in this exhibition of show-stoppers, it was one photo where a woman lies on a hardwood floor with her legs kicked up in the air, her hands reaching up to grab her heels in an ultimate “do me” pose. Her arms and legs are tied together as if to seal her available condition. Her head is completely obscured and the ropes give the impression of tied-up meat or a stitched together assemblage of Hans Bellmer body parts. A vibrator has been inserted into her vagina. We presume that it is “turned on” because we see it tethered to it’s battery-powered controller lying on the floor, and because the picture allows us no other realistic choice. As if to power the point home, on the floor lies another vibrator, still sheathed in a used condom, as if it had been castrated in flagrante delicto. The two vibrator cords are mildly tangled up with each other, and together with the slack power cord of a lamp in the background, they all seem to be mocking the taut ropes that bind the model. Near the vibrators is a rubber lizard, its mouth agape, poised between a lascivious grin and a heckling laugh. More threatening than a snail, yet much less self-consciously artificial than Godzilla, the lizard on the periphery of the action is a stand-in for a Warhol-like Araki that we know instinctively is just off-frame, turned on by the spectacle, and turned on by his control of the power cords.

Beyond the ropes and these props however, it is with his paint — the paint that is after all this show’s reason for being — that Araki gives us his final coup de grace. Unlike the majority of the works in the show and accompanying catalog, where the paint is applied relatively sparingly, here the entire canvas of the original print seems to have been stained with some sort of yellowish layer of paint. Since it shows up most clearly against the naked white body of the tied-up model, it gives one the further impression that this is no longer a woman on the floor but mere body parts, as if they were soaking in formaldehyde. But Araki doesn’t stop there. He has painted a circle around the model. This circle, even as it marks her as the haloed/hallowed focal point around which the tawdry props revolve, also demarcates the limits of her existence. Of course the shoot will end, and the model’s rope burns will fade with time, but as canvas she will, like Rauschenberg’s goat, be trapped in that circle, the paint mixing with silver gelatin to fix her twice.