Martin Gropius Bau Niederkirchnerstraße 7, Corner Stresemannstr. 110 10963 Berlin Allemagne

Asked why she didn’t photograph mountains or landscapes, Herlinde Koelbl once replied: “People are unpredictable.” Perhaps this statement gives an indication of what makes the work of this great German art photographer so special. She wants to grasp people, understand them, find out something about how they live, what they choose to surround themselves with, how they would like to appear and what they really are, what elates them and what casts them down. Her images are intense experiences because they are the product of a genuine interest in and curiosity about her fellow human beings, and her respect for the lives of others is always in evidence. In her photographs no one is stripped naked, but they are subjected to searching questions. This applies just as much to Gerhard Schröder as to any married couple sitting in their living room.

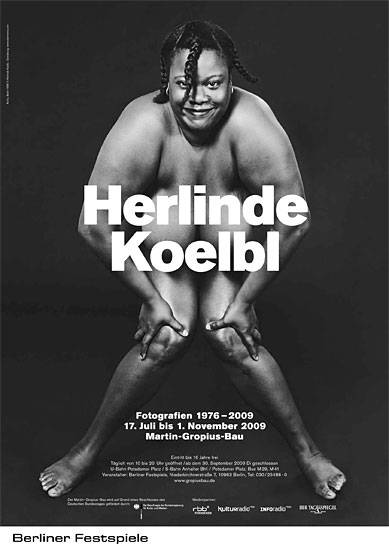

For over thirty years now Herlinde Koelbl has been working on a sweeping novel of our times. As each successive chapter is added one has the impression that all her projects are links in a chain. Now, for the first time, an exhibition is to be seen in Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau which shows the work of Herlinde Koelbl in all its variety. In the past our knowledge of her work was at best fragmentary. In addition to icons of portrait photography there will be plenty of surprises and experimental work.

It was sheer chance that made her take up photography. In 1976 a friend made her a gift of four films that she used to photograph her children playing. She was quick to realize that this was the medium for her. She wasted no time wondering about what models to follow. She did not want to be trapped in someone else’s style, but to develop one of her own as soon as possible. Gradually she acquired the necessary equipment, although she knew from the outset what her particular interests would be: patterns of living and behaviour. Soon afterwards her first colour feature (on Bavarian markets) appeared in Stern.

In 1980, almost with an ethnologist’s detachment, she took a good look at the German drawing room, “into which people invite others in order to show off what they have”.

Anyone who found the idea banal at first soon found themselves confronted with photographs which say a lot about people and their spaces, who have furnished their sitting rooms as often as not with others in mind – as status symbols, as settings of success, and codes of belonging. Conceived almost as a pendant to this is her “Photographic Bedroom Tour”, which was created later and with which she would travel the globe. Even these glances into the most intimate corners are neither voyeuristic nor titillating, but indicative of a gift for uninhibited depiction. In a manner peculiar to few other photographers Herlinde Koelbl captures the personality of an individual because she looks for clues in the environment, in everyday realities and, of course, in the sitter. And if the lens proves inadequate, she enlists the aid of a tape recorder or film camera in order to answer what she regards as the only valid question: Who is this person? In this she succeeds magnificently in the “Jewish Portraits”, on which she has been working for five years. Long before Steven Spielberg she told a story of Holocaust survivors of whom the youngest was 70 and the oldest 94. “This series is a milestone in my personal life. The faces revealed so many traces of hardship, so much sadness, yet so much wisdom and humility as well,” says Herlinde Koelbl. In the course of their conversations she learns about their terrible fates, but she also learns from such people as Erika Landau or Norbert Elias, from Josef Tal or George Tabori, what it means to live without bitterness and hatred. “Hatred,” says Erika Landau, “destroys the hater himself. It has a boomerang effect.” She was to be grateful for these encounters, which cost her some effort. Bruno Kreisky and Josef Tal would become valued friends, as their first conversation was to be followed by many, many more – some of the rewards of her profession.

Germany’s first wide-ranging exhibition will attempt to shed more light on the Herlinde Koelbl phenomenon. The approach will not be chronological, but thematic. Anyone who talks to her about such things as housing, loneliness, work or violence soon notices that she is a conceptual artist in the best sense of the term. If she needs anything to back up her statements she’ll use it. And she is always trying out new things, seeing how far she can go, testing ideas for practicability. Almost unknown are her abstract works that emphasize traces of transience – cracks in a road surface or pieces of charcoal with fascinating patterns: traces of the beauty of things that constantly crop up in her work. “My thinking,” she says, “was always forward-looking. I set my own standards, allowed myself to take a different view of things. Once an artist starts speculating about how his work will be received, he is lost.

This freedom of thought, the freedom to do my work as I see fit, has always been of quite extraordinary importance.” When a publisher tells her that something has to be a paying proposition, she bristles.

This was the case with “Traces of Power”, perhaps the most important long-term study of the elites of the Federal Republic of Germany. Precisely because her “sittings” were not designed to distinguish between who was socially important and who wasn’t, as the first thing she looks for in her sitter is the human being, she managed to get very close to fifteen of this country’s foremost personalities, including Angela Merkel, Gerhard Schröder and Frank Schirrmacher. Closer than anyone before her. And no doubt closer than any who may come after her. For eight years she pondered the question of how high office changes people, of whether it distorts the personality and, if so, how, where addiction begins and when withdrawal symptoms set in. She was particularly successful in bringing out the veteran Green and later foreign minister Joschka Fischer. Herlinde Koelbl peels of the various layers of this politician, traces how he constantly reinvents himself in order to live up to his role, and is a witness to his honest confessions concerning the fallings out he brought about in his private life. Never has Fischer seemed more authentic as when seen by Koelbl. Today he would probably give no more interviews dealing with his fears, his failures, his frustrations, and his women. One can see from his shifting postures how Fischer retreats back into his shell, and the statesmanlike gesture becomes more important than the frank avowal. For over eight years Herlinde Koelbl occupied herself intensively with those in positions of power, collecting newspaper clippings about them. “I have come to understand a lot about power structures, about their advantages and disadvantages, about ego gratification, and what it takes to stay at the top,” she says. “Traces of Power” is a fascinating attempt to keep testing how the normal claim to power becomes self-perpetuating. Herlinde Koelbl manages this with closeness and distance. For over thirty years now Herlinde Koelbl has been on a photographic journey in the most literal sense, for she has always thought in global terms. Now she is stopping over in Berlin and combing her archive for works that go beyond the merely topical. Many, very many of them have lasting validity, have seared themselves into the collective memory, while others are snapshots that still have a lot to say about the deeper aspects of life which are so important to the art photographer. “I am interested in people. But it has to go further than just scraping the surface. That is the whole secret.” And, one might add, the artistic credo of Herlinde Koelbl.

Ingolf Kern