While the sound of vuvuzelas greeted the first World Cup goals at South African stadiums, the Johannesburg National Gallery celebrated Without Masks: Contemporary Afro-Cuban Art, the first show of Cuban art presented in this country. Cuban critic Orlando Hernández, curator of the exhibition, graciously agreed to an interview about the exhibition and its origins.

Does an Afro-Cuban contemporary art exist? And if so, how does it differ from explorations of Afro-Cuban themes in the 1930s?

This exhibition and its catalogue attempt to show the different approaches that Cuban art has taken, over the past 20 or 30 years, to what we call our “African legacies,” or the African features of our cultural identity. These approaches explore not only religious themes—which are among the most frequent topics—but also social and individual aspects of this heritage. By that, I mean the presence and status of the black and mixed-race populations in our society, which are still affected by European and colonial practices of racial discrimination and racism. Other links with Africa have also been addressed, of course, such as the participation of Cuba in the Angolan war.

By the act of selecting artists and works, I inevitably propose the existence of “an Afro-Cuban contemporary art.” It is not a major departure, but rather the recognition of a long-continuing creative process. In the mid-1990s, this process took on new characteristics: a greater interest in reflecting on the social and political aspects of race relations, and a tendency among some artists to be more refletive, more committed, and in some cases more combative.

During this period and even earlier, with the 1980s generation, the depiction of “Afro-Cuban-ness” turned away from the superficial, colorful, consciously exotic treatments that characterized much of the “Afro-Negrismo” of the 1930s and the later work that it influenced. Currently, though, younger generations of artists seem to have lost interest in these themes, which could be interpreted as a temporary setback.

Maybe Without Masks—like Queloides: Raza y Racismo en el arte cubano contemporáneo (Keloids, Race and Racism in Contemporary Cuban Art), the exhibition curated by Alejandro de la Fuente and Elio Rodriguez, which was recently presented at the Wifredo Lam Center in Havana and opens this fall at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh--will encourage artists to address these issues in our visual arts again. When I talk about contemporary Afro-Cuban art, I am interested in “the contemporary” being understood as a broad temporal spectrum related to the present and past, as well as to the “reality” and the importance of those problems that are expressed in art, as opposed to mere language innovations belonging to the realm of appearance and aesthetics.

We must not confine Afro-Cuban art to a separate group of artists, like a ghetto, a community, or a brotherhood. “Afro-Cuban-ness” hasn’t had much to do with artists (with racial identity or the skin color of the artists, for instance), but with the character and intention of their works. They are components of Cuban identity, even when they are almost invisible. It is not even necessary to show perseverance or loyalty to those issues, which happens less often (Mendive, Olazábal, etc.). All of this dramatically enriches and broadens the cultural panorama. It includes rather than excludes.

For the determination of an “Afro-Cuban art,” it is necessary to make a careful selection within this universe we have always called “Cuban art.” The important thing is to recognize that that the supposedly generic character accorded to Cuban art has actually been Euro-centric, and therefore full of elitist, racist, and colonialist elements. What we have tried to do in Without Masks is simply to go on with the conscious, deliberate selection process as a way of counteracting or correcting that situation, and to propose other readings of Cuban art.

Which artists were included? How many pieces, and in which mediums?

Currently, the collection has more than a hundred pieces by 26 artists. The works include painting on canvas and wood, watercolor, engraving (xilography, silk-screen and colography), collage, patchwork, sculpture, soft sculpture, installation, video installation, photography, and video art. Artists were organized in the exhibition and catalogue according to a hierarchy traditionally used in Afro-Cuban religious traditions: first, those already deceased, followed by the elders down to the youngest. That's the order we followed.

Here’s the list of artists in the exhibition: Ruperto Jay Matamoros (Santiago de Cuba 1912- Havana, 2008)/ Belkis Ayón Manso (Havana, 1967-1999)/Pedro Alvarez Havana, 1967- Tempe, Arizona, 2004)/Manuel Mendive Hoyo Havana, 1944)/ Julián González Pérez (Havana, 1949)/ Bernardo Sarría Almoguea (Cienfuegos, 1950)/ Santiago Rodríguez Olazabal (Havana, 1955)/ Ricardo Rodríguez Brey (Havana, 1955)/ René Peña (Havana, 1957)/ Moïses Finalé Aldecoa (Matanzas, 1957)/ José Bedia Valdés (Havana, 1959) /Marta María Pérez Bravo (Havana, 1959)/ Rubén Rodríguez Martínez (Matanzas, 1959)/ María Magdalena Campos-Pons (Matanzas, 1959) / Juan Carlos Alom (Havana, 1964)/ Elio Rodríguez (Havana, 1966) / Carlos Garaicoa Manso (Havana, 1967)/ Oswaldo Castillo Vázquez (Santiago de Cuba, 1967)/ Alexis Esquivel Bermúdez (La Palma, Pinar del Rio, 1968)/ Armando Mariño (Santiago de Cuba, 1968) Ibrahim Miranda (Pinar del Río, 1969)/Alexandre Arrechea (Trinidad, 1970)/ Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy (Havana, 1971)/ Douglas Pérez Castro (Santo Domingo, Villa Clara, 1972)/ José Angel Vincench Barrera (Holguín, 1973)/ Yoan Capote (Pinar del Río, 1977).

This exhibition was drawn from a private collection. Could you tell us more about it? The collection was started in November 2007, thanks to the interest of London-based South African businessman Chris von Christierson. Given that he and his family were born in Africa, it seemed like an excellent opportunity to focus on the particular area of Cuban art devoted to exploring the links between Africa and Cuba. Fortunately, Chris agreed to the idea of building a private collection with a public touring-exhibition component.

It’s not easy to find a private collector willing to devote his money and energy to this kind of project, especially in these difficult economic times. Generally, collectors invest their money in renowned artists, not in the social, political, or cultural importance of a specific topic. Having the opportunity to build such a collection has been a privilege. This is the only collection with both a private and an institutional character that is devoted exclusively to Afro-Cuban art and that has many different artists, most of them renowned at the international level. In this collection, they share stage with little-known folk artists and self-taught artists. Unfortunately, even in Cuba we have no collection of this size and character.

Going forward, the collection will be enhanced by the addition of new artists and works reflecting emerging trends—artistic expressions, perhaps, that fall outside Western concepts of art. The collection is a work in progress, an ongoing process of artistic investigation, of growth.

Could you give us some details about the exhibition preparation and installation, and the opening? Who was involved on the South African side? And in Cuba?

I organized the collection with my wife Lucha, and the von Christierson family, especially Chris and his daughter Nadia.

We were interested in a basic working team with a tight set of perspectives: private collector, freelance curator, and individual artists. Above all, we wanted to value individual expression over institutional, in projects that addressed not only artistic and cultural topics, but social and political issues as well, in a way that avoided any form of censorship.

The collection premiered at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in South Africa, the most prestigious museum in the African sub-continent. It opened on May 23, Africa Day, and will run through August 29, 2010.

More than specific individuals involved with the show, I’d like to mention the people of South African, who were very receptive to the topics addressed in this project. They participated not only as visitors to the exhibition but in public debates on different topics—racism, religion, etc.—that we organized in collaboration with invited artists (José Bedia, René Peña, Elio Rodríguez, Roberto Diago, and Douglas Pérez). We cannot forget that this country rid itself of Apartheid only a few years ago. But despite their victory (the racial democracy of a “rainbow” country), there are still traces of inequality.

I think that the Cuban example, where half a century after the socialist revolution there is still not still a true racial democracy, was quite revelatory and very instructive.

Tell us about the exhibition catalogue.

The catalogue (for the moment, available only in English) includes all works in the exhibition as well as an essay on each artist, and brief explanations about most of the works so the public can better understand them. It was done in record time: around two months, including the introduction, the 26 essays, the English translation, corrections, editing, design, and printing, etc. I myself am very surprised at these results.

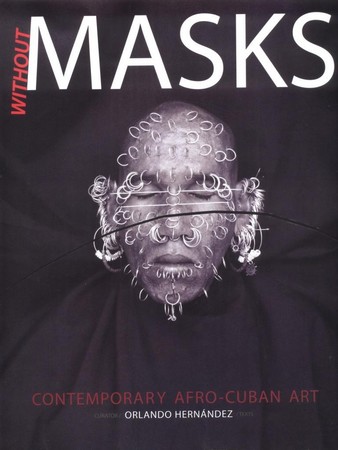

The cover is a photo by Juan Carlos Alom, which was in line with our purposes—provocative enough. It shows the face of a popular Havana personality, full of piercings. It is like a mask but is unquestionably a face, and also suggests “tribal” references of African origin.

Will Without Masks travel to other venues? If sponsorships can be arranged, we’d be interested in taking it to African or Afro-American countries—or to other places experiencing racial conflicts or intolerance to traditional African religions—to promote interest and reflection on such issues. We thought about other South African cities like Cape Town and Durban, which even asked for it, but the resources to do this have not turned up so far.

Then we began to make arrangements to take it to Sao Paulo, Brazil, which is home to an important Afro-Brazilian museum. However, the collection will be probably taken first to London and exhibited there. It all depends on complicated financial factors.

Written by: Abelardo Mena, Cuban Art News